|

|

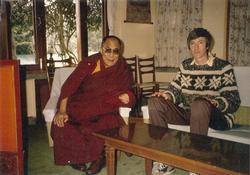

| William Cox, M.D., meets with His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India (February 1992) |

|

The "Great Yeshi Dhonden" is how I've heard him described. A simple and humble maroon-robed monk, he is the former personal physician to the Dalai Lama and the senior and most famous practitioner of traditional Tibetan medicine. He now ran a busy private clinic in Dharamsala, India -- home to the Tibetan government-in-exile and a large Tibetan refugee population. It was February 1992, and I would be spending the morning at his side, observing.

Tibetan medicine is based on the Buddhist Medicine Tree and its associated Tantras. It is vastly complex, yet its basis is simple. There are three humours that permeate all sentient beings: bile, wind and phlegm. When they are in balance, we are healthy. Yet the slightest imbalance may account for the tens of thousands of diseases documented in the Tantras. The practitioner diagnoses the disease and prescribes the appropriate treatment to restore the balance, thereby restoring health. Tibet's first medical school was built in the 8th century, but Tibetan medicine was almost certainly long established by then.

The premier diagnostic tool is pulse diagnosis. Studied for a solid year, it is said to take 10 years to master. The middle three fingers are placed on the patient's radial artery at the wrist. Each presses down with a slightly different pressure. The inside and outside of each finger senses, or "reads", a different organ system (a division into hollow and solid organs does not necessarily correspond to Western medicine's understanding of anatomy). The combination of the humours is also read. There are hot and cold illnesses, seasonal pulses, and more.

Next, the urine is examined and smelled. It is whisked and the way it bubbles or froths is noted. Finally, a prescription is written in Tibetan and the patient is sent to the pharmacy.

Dr. Dhonden saw dozens of patients that morning. There was very little doctor-patient discussion. It was as if Dr. Dhonden already knew why they came to see him and what to look for. Pulse diagnosis and urine examination seemed to be the mainstay, followed by more particular techniques that might be necessary. I watched him do facial acupuncture on a young monk.

Yeshi Dhonden has been to the big medical centers on the American East Coast and examined patients. His diagnostic abilities stunned University hospital doctors! His descriptions, translated from Tibetan, left his American medical colleagues no doubt they were talking about the same disease or underlying congenital anatomic defect.

Tibetan medicine is mostly herbal, and I followed the last patient of the morning over to the pharmacy where it was prepared and distributed. The raw materials were mostly gathered from the surrounding valleys and hillsides and assembled into the final product in this building. A strong but wonderfully pleasant herbal scent filled the air, like potpourri, and I wondered if it might be acting as a heath-enhancing tonic on the workers who inhaled it all day. In one of Dr. Dhonden's final exams as a student, he was taken into a large tent near the medical institute in Tibet where he trained. Long tables were filled with roots, leaves and herbs of every kind. Blindfolded, he identified every one correctly by taste, smell and touch!

Early the following afternoon I showed up at the office/apartment of Dr. Tenzin Choedrak, the personal physician to His Holiness the Dalai Lama. This small, gentle man was imprisoned and brutally tortured by the Chinese Communists in Tibet before he was able to make his way to India. His smile filled the room with compassion as he took my hand in his, holding it and rubbing it gently until it reached the same temperature as his. His skin was the softest I ever felt.

A Nepali woman knelt beside us to translate, but I had no medical issues and said nothing. I just wanted to experience having my pulse taken ... and who better than the Dalai Lama's personal physician to do it! Dr. Choedrak pressed his three fingers against my radial artery.

After what seemed like several long minutes of concentration, he removed his hand, looked at me and, through the translator, announced that I was suffering from constipation and maybe a mild gastritis. I was stunned! While virtually every westerner travelling in India gets diarrhea on one or more occasions, I'd been having the opposite problem. My bowels had been stopped up for several days, despite indulging in street food, and I was beginning to get concerned. As for the gastritis, it was almost 2 pm and my stomach was quietly rumbling with hunger. I went to the pharmacy of the Tibetan Medical and Astrological Institute and filled the prescription Dr. Choedrak gave me.

A final word to the wise: Don't mix Tibetan medicine, Larium (a vicious anti-malarial known to cause hair loss and exacerbate psychotic episodes) and strong, dark Indian rum! It caused me to miss rounds at Delek Hospital the following morning!

|

|

|