|

|

| Quentin and Desiree Simeon with their daughters, Ashlynn and Stormy. |

|

Being a non-White man is difficult no matter where you grow up in America. I don't mean to say that being a White man or woman doesn't have its problems, but being White definitely has its advantages. I lie upon the thin line that separates the Caucasians from the Inuits, Indians and other non-Caucasian races. I am a half-breed born to half-breed parents, half Alaskan Native, Athabaskan and Yup'ik, and half European, German, Russian and English.

Separation

Through the years, I've noticed that I'm treated differently by both my Caucasian and Native peers, but I cannot really call them peers, for they seem to be in separate classes. Being raised in the White culture, people label me a foreigner in the villages of rural Alaska, even in the village where I grew up, on the Kuskokwim River. I would imagine that other Natives raised outside the Village share a similar perspective. The White culture is much different than rural Alaskan culture. When any Native, half-breed or whatever enters a developed community like Anchorage for the first time, they are literally foreigners. Being a half-breed, caught between two cultures, is not easy. We have to be more Native than the Natives and Whiter than the Whites.

Elementary School

In the early eighties, racism was still a major problem for Alaska Natives living in the developed communities of Alaska. When I was in third grade in Bethel, Alaska, we Native students were segregated from the White-looking kids, some of whom were my cousins and just as Indian or Inuit as I. But all of them were fair skinned and left in the White class. All of the other Native kids who were dark in complexion, including myself, congregated in a different class with a Native teacher, while the Whiter-looking children were kept together in Mrs. Ballay's class, who is also White. When I told my mom about everyone in my class being Native, and everyone in my best friend's class being White, she had to investigate. My mother went down to my school and demanded that I attend Mrs. Ballay's class with all the White children. My mom was not going to have her child treated any differently than the White kids.

Feeling Dirty

When I realized I was the only dark-haired child in Mrs. Ballay's class, I remember feeling different and dirty somehow, maybe because of my darker complexion. Being the only dark student, I felt ashamed, and eventually my self-esteem fell through the floor.

Now, after some reflection, I think that the teacher and the administration resented me because I broke the mold of Native students by attending the 'White class.' After a whole year in Mrs. Ballay's White class, I did poorly in the rest of my schooling until I left Bethel in 1994 for the 'Big City' of Anchorage, Alaska. I don't know if the problems that I faced in school were because of my color, but I know that I did better in school while enrolled in the Anchorage School District where I was not labeled as White, Black or even Brown. In Bethel I was not even accepted by my own brown people, because they thought I had left them for the Whites. Many half-breed Native Alaskans, depending on their complexion, choose either the Natives or the Whites. I was not willing to segregate myself from either group. I am proud to be me, but it hurt to be in both places while not being in either. This pain was felt deeply, so deeply that I did not realize it was a source of the soreness in my soul.

Being Poor in Anchorage

When I arrived in Anchorage, I started a much-needed healing process, because of the latent turmoil in my tannish-brown soul. In Anchorage, I was free from the persecution of being an Alaskan Native man, or so I thought. While living in Covenant House in downtown Anchorage I was exposed to the harshness of life on the cold streets.

|

| Self-portrait of Quentin and Desiree Simeon, by Quentin Simeon. |

|

In the summer of 1994, my friends and I were so poor that we would buy one ticket for a movie, sneak each other in, and watch movies all day long, usually on Saturdays. Needing a movie schedule, I went to McDonald's in the early morning of a Saturday. Not having any extra money, not even fifty cents for a newspaper, I approached a man who was sitting alone at a table who had apparently discarded the movie section by leaving it on the floor. When I asked the man if I could use the section containing the movie listings, he stated that he didn't want anything in his possession to be sullied by Native hands. His vulgar statement shocked me, because I didn't think that a person would have been so blunt and truthful about their racism. But I learned what sullied meant and use the word to this day.

Not Native Enough

After I completed High School and returned to Bethel and my other hometown, Aniak, which are both on the banks of the Kuskokwim River, I noticed that I suffered another form of prejudice, being an outsider. Because I had spent so much time in urban Alaska, my relatives believed that I had lost a part of my rural self. When my relatives in Aniak brought me fishing and hunting they treated me like I was no longer capable of pulling my own weight in the bush; the older men would scoff when I made a simple mistake.

Moose Hunt

During the last day of our moose-hunting trip, my Uncle and I were coming around a bend in the river when we came up to a moose running into the brush. I rushed to the front of the boat, which was moving around thirty miles an hour. When I got to the bow with my rifle, I pulled off two shots. While in mid-squeeze of the second, we hit a drowned log in the middle of the river. I almost shot a hole in the boat, not to mention almost falling in the river. Well, I missed the moose by a long shot. My uncle was not at all concerned about me; he was only concerned if there was a hole in his bow. He even scolded me for being so clumsy, even though he was the one who hit the log. I felt like I'd never prove myself as a valuable member in the family, but I tried over and over to gain his respect.

Shooting Birds

The next year, after the river broke, my dad, uncle and I went goose and duck hunting. In the morning, we set out and went zipping up and down the river looking for water foul. We spent a good part of the day out on the river and throughout that time we had been pretty lucky. I caught 16 ducks and geese with a single-shot 12 gauge, while my uncle caught only six with a pump 12 gauge. I had finally gained stature in my uncle's eyes by humiliating him on the river, where he had lived his whole life. My uncle is a proud and prosperous hunter, and is still sore that I beat him, but he respects me now.

White Man Skills

Proving myself to the White community has been much more difficult. To this day, I am not seen as a good citizen or even a law abiding one. On June 12, 1997, I was pulled over for bald tires while driving down the Glenn Highway. The only discrepancy was that my tires weren't bald at all. I also didn't know how an ordinary human being could tell if the tires on a moving vehicle were bald or not. It must be one of those White man skills, I thought. Because of my age, gender and race, I knew the police would pull me over for only one apparent reason -- I fit a stereotype.

A White Light

|

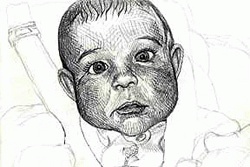

| Portrait of Stormy Simeon by Quentin Simeon. |

|

I have been pulled over so many times for menial things like not having my front license plate displayed properly or for turning into the middle lane instead of the left or right. One of the incidents that stands out was on my friend's birthday in 1996; I was pulled over because the tape on my right rear indicator was peeled ever so slightly and the officer said he could see a small amount of white light emitting from the indicator. The officer happened to be next to us at the intersection, prior to pulling us over. I remember looking at him and knowing that he was going to do something to us young Native men who were just on our way to Pizza Hut. I don't know the real reason the officer pulled me over, but I doubt it was the indicator, which was the only thing for which I was ticketed.

A Fine Line

As a half-breed, I walk a fine line between two worlds. If I'm not careful that line could cut me in two. I appreciate my genetic diversity; I wouldn't have it any other way. I have had a lot of struggles, almost like a tug of war between two cultures. At times I believed that it would tear me in half because I refused to lose any part of my half-breed self. I will continue to succeed in proving myself to both worlds in spite of the obstacles that have hindered my progress. I will never let anybody belittle my existence because I now know that I am just as good as any White man or rural Native.

|

|

|