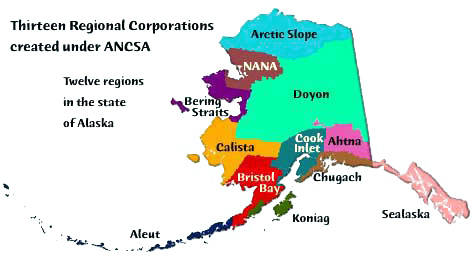

| In 1971 the push for oil development, the state's desire to get the land promised to it under the Statehood Act and the Alaska Natives' efforts to save their land paid off with what would become the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, known as ANCSA. For four long years spirited debate had focused on just how much land and cash the Alaska Natives would be granted for the settlement of their claims. The final bill that emerged promised 44 million acres and $1 billion in cash. People There were nearly 80,000 Alaska Natives alive on December 18, 1971, who could participate in ANCSA. Most of those affected by the act were in Alaska, but about 20,000 people lived in the Lower 48 and even other parts of the world. "Native" was defined as a citizen of the United States with one-fourth degree or more Indian, Aleut or Eskimo ancestry, born on or before December 18, 1971, including Natives who had been adopted by one or more non-Native parents. Amendments were passed later to allow Native corporations to issue stock to those born after December 18, 1971. In general, this has been done through the creation of a new type of stock, known as "life estate stock." This stock is valid only during the shareholder's lifetime and cannot be passed on. Only a few corporations have extended stock ownership to those born after 1971. Structure The corporate structure of ANCSA was a departure for Congress. Former Cook Inlet Region, Inc., President Roy Huhndorf has described ANCSA as an extraordinary national experiment in federal relations with Native Americans. He points to the fact that corporations, not reservations, were organized to administer the proceeds from the historical land claims settlement for Alaska Natives. Alfred Ketzler, who was President of the Tanana Chiefs Conference when ANCSA was under consideration in Congress, discussed the corporations in a letter to the editor of the New Republic: "Native leaders in Alaska have given great attention to the structure of the settlement, the means of administering the land and money. Indeed the concept of the development corporation is ours, though we would divide the land and money among three levels of business corporations, local, regional and statewide, in keeping with the pluralism of American society and economy." Thirteen regional corporations, including 12 in Alaska and one that was created later to represent Alaska Natives living outside the state, were created. Alaska Natives who enrolled were made shareholders when they received 100 shares of stock. The size of the regional corporations ranged from Ahtna, Inc., with about 1,000 shareholders, to Sealaska Corporation, with about 16,000 shareholders. Others included; The Aleut Corporation; Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; Bering Straits Native Corporation; Bristol Bay Native Corporation; Calista Corporation; Chugach Alaska Corporation; Cook Inlet Region, Inc.; Doyon Ltd.; Koniag, Inc.; NANA Regional Corporation, Inc.; and the Thirteenth Regional Corporation.  |  | Approximately 220 village corporations were created under ANCSA, and villages were given a choice as to whether they wanted to incorporate as profit or nonprofit entities. None chose to be nonprofit. The reason for this is that the corporations were founded under state law, which didn't allow nonprofits to pay distributions to members. A profit corporation, however, was authorized to pay dividends to shareholders from profits. Alaska Natives who enrolled to their village received 100 shares of village corporation stock. Those who elected not to enroll in a village corporation, but enrolled in a regional corporation were called "at-large" shareholders. There was a lot of confusion over enrollment, but generally speaking, Alaska Natives were allowed to enroll to the region and village where they grew up and which they considered home or to the region where they were living at the time the act was passed. Because Cook Inlet Region, Inc., was based in Alaska's largest city, CIRI became a "melting pot" for all Alaska Native groups. Many Alaska Natives from other parts of Alaska who moved to Anchorage signed up for CIRI. The size of villages ranged from 25 people to about 2,000. The larger village corporations, each of which included about 2,000 people, were Barrow, Nome, Bethel and Kotzebue. Amendments passed in 1976, authorized village corporations to merge with each other or with the regional corporation. Some villages have merged and created new corporations, such as the Kuskokwim Corporation in the Calista Region, MTNT and K-oytl-ots-ina Limited in the Doyon Region; the Alaska Peninsula Corporation in the Bristol Bay Region; and Afognak Native Corporation and Akhiok-Kaguyak Incorporated in the Koniag Region. All the villages except Chitina in the Ahtna Region merged with Ahtna; and all the villages in the NANA Region except Kotzebue merged with NANA. At least two villages distributed their assets to the village tribal government, and that was done by Venetie and Arctic Village. The structure has become the source of heated debate for many years. Money The amount of money distributed through ANCSA was $962 million, which was essentially determined on a per capita basis. It came from both the State of Alaska and the Federal Government over a period of about 11 years. The long timeframe for distribution greatly diminished its value due to inflation. In the first five years, 10 percent of the money distributed went to all individuals who were shareholders. The regions retained 45 percent of the total, and the remaining 45 percent was distributed to the villages and the "at-large" shareholders on a per capita basis. At-large shareholders were those who enrolled only to a region and not a village. After that, the money was distributed 50-50 with half retained bythe regional corporations and half distributed to the village corporations and at-large shareholders on a per capita basis. A provision of ANCSA, Section 7(i), requires that regional corporations share 70 percent of their resource revenues among the corporations. This section is an extremely unusual aspect of ANCSA and it took the corporations about 10 years to hammer out an agreement that spelled out exactly how this would be undertaken. The concept was sound - find a way to make sure that resource-rich corporations shared with those who were resource-poor simply by accident of location. But once lawyers and accountants got involved in the implementation, it nearly broke the bonds holding Native groups together. Only after the Native leadership took control of the issue themselves was it resolved in a harmonious manner. Land The land conveyed under ANCSA was 44 million acres, which was a little more than 10 percent of the entire state. It sounds like a tremendous amount of land, especially when compared to treaties the United States made earlier with American Indians. When viewed as what was granted to the people who had a valid claim to the entire state, however, the settlement seems relatively small. Of the 44 million acres, 22 million acres of surface estate went to village corporations on a formula based on population - not per capita. This land was generally located around the village itself and consisted of prime subsistence areas. The subsurface estate of this land went to the regional corporations. Sixteen million acres went to the regional corporations, and that included both the surface and the subsurface estate; and two million acres was conveyed for specific situations, such as cemeteries, historical sites, and villages with fewer than 25 people. Another four million acres went to former reserves where the villages took land instead of land and money. These former reserves were granted land entitlements ranging from 700,000 to 2 million acres. They included Gambell and Savoonga on St. Lawrence Island, Elim, Tetlin, and Venetie and Arctic Village. Klukwan originally opted for this provision, but leaders there later changed their minds. Not affected by the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act was Metlakatla on Annette Island in Southeast Alaska. Metlakatla was a reservation before ANCSA, and remained one afterwards. A final note: The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act is a very complex document that has inspired people over the last three decades to write thousands of pages about it. The act has been praised, and it has been roundly criticized. But what's really important to keep in mind when discussing ANCSA is that it is a document that was developed for a group of human beings who had a very real claim to their ancestral home in Alaska. Their connection to the land is a spiritual one that transcends complex regulatory schemes. And yet for many, their tie to the land today is a law passed by Congress on December 18, 1971. |

|

|