|

The following is excerpted and adapted from Searching for Steinbeck’s Sea of Cortez: A Makeshift Expedition Along Baja’s Desert Coast by Andromeda Romano-Lax (Sasquatch Books, September 2002)

Steinbeck's Sting

By Andromeda Romano-Lax

|

| Cover art courtesy of Sasquatch Books |

|

John Steinbeck was inspired to write one of his most famous stories, The Pearl, after visiting La Paz. He heard the folktale in Baja, briefly summarized it in the Log, then spun it into a book-length parable a few years later. The legend of the pearl was just one of many things he took away from the Cortez—one of the stories, settings and symbols that fed his later work for a decade.

We decided to read The Pearl aloud one afternoon as we sailed. The kids listened eagerly. So did our captain, Doug. Brian and I had read this story many years before—the story about the great pearl, how it was found and how it was lost only after it had torn a hole in the lives of a simple Indian family. On first reading, it had seemed overdramatic and outdated. Now, we read it in Baja and it seemed less an overwrought parable than a starkly realistic account.

As always, Steinbeck took great care to describe his natural setting: the Baja he came to know well in 1940. In many ways it was the same Baja we’d been sailing and walking and tidepooling for weeks. “The beach was yellow sand, but at the water’s edge a rubble of shell and algae took its place. Fiddler crabs bubbled and sputtered in their holes in the sand. ... Spotted botete, the poison fish, lay on the bottom of the eel-grass beds, and the bright-colored swimming crabs scampered over them.”

Aryeh, age 5, and Tziporah, barely 2, nodded — crabs, yes, and botete. Harry Potter, our other read-aloud, was fantasy. This was life. For young Tziporah especially, whose toddler memories barely held for more than a week or two before blending or fading, the setting seemed like everything she had ever known.

In the story, Kino finds an enormous perfect pearl, “the Pearl of the World.” First it attracts friends: the doctor who will treat their ailing son now that the Indian family has credit, and the priest who will finally marry poor Kino to his common-law wife Juana. But these are only false friends. The pearl arouses envy. It leads to discontent and violence. The town’s pearl appraisers, in collusion, refuse to offer Kino a fair price for the treasure. Men arrive in the dark of night to steal it. This gift from the gods, which should have bought Kino happiness and health and leisure, instead robs him of friendship and security. It threatens his family, muting the happy little “Song of the Family” which runs like a current through the story.

“All manner of people grew interested in Kino—people with things to sell and people with favors to ask. ... The essence of pearl mixed with essence of men and a curious dark residue was precipitated. Every man suddenly became related to Kino’s pearl, and Kino’s pearl went into the dreams, the speculations, the schemes, the plans, the futures, the wishes, the needs, the lusts, the hungers, of everyone, and only one person stood in the way and that was Kino, so that he became curiously every man’s enemy.”

|

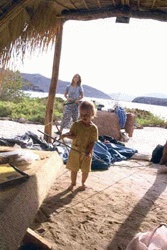

| Tziporah helps collapse tent poles under the shade of a beach palapa as Andromeda breaks camp. |

|

Steinbeck, whose The Grapes of Wrath had become a recent bestseller — attracting death-threats and notoriety — had seen how new wealth and fame could drown out the sweet, simple “Song of the Family.” Kino had struck Juana when she tried to get rid of the poisonous pearl; John had alienated and cheated on his wife, Carol. In Baja, Steinbeck was still mulling over all he had lost and all that he soon would lose, so that when he heard the parable of the Pearl it stuck to him like a cactus burr, implanting itself in his imagination. At the end of Steinbeck’s story, Kino reclaims his life by throwing the Pearl of the World back into the ocean. The treasure that was never meant to be sinks under the waves, rejected. Steinbeck tried to do the same thing with his fame. While Grapes still dominated the bestseller charts, Steinbeck turned away from fiction and headed south to Baja, to write The Log from the Sea of Cortez — a very different kind of book.

These parallels fascinated Brian and me. But Aryeh and Tziporah were intrigued by a different aspect of the story — the very beginning. The Pearl opens in cinematic style (Steinbeck was experimenting with cinema when he wrote it) with the “camera” fixed on Kino and his awakening family. As Kino opens his eyes to the dawn light, his eyes become the lens, panning across the simple brush hut to observe his dark-eyed wife Juana. Kino looks to the hanging box where his baby son, Coyotito, sleeps. The Indian couple proceeds silently with their morning routine. The sun warms the brush house, “breaking through its crevices in long streaks.” Then one of those streaks falls upon the ropes of Coyotito’s hanging basket. A tiny movement there on the ropes draws Kino’s and Juana’s attention. They freeze.

The scorpion moves down the rope toward the baby box. Under her breath, Juana utters an ancient magic spell and then on top of it, just for good measure, a Hail Mary. Kino glides toward the box and reaches for the scorpion. The scorpion, sensing danger, stops, and its tail rises up over its back in little jerks and the curved thorn on the tail’s end glistens.

As we read the story aloud in the Zuiva’s cabin, Aryeh and Tziporah leaned forward on their bunks, both wanting and not wanting to hear its resolution. “And then what?” Aryeh asked.

“And at that moment,” I read quickly, trying to get the worst of it behind us, “the laughing Coyotito shook the rope and the scorpion fell.”

The scorpion stung the baby. A collective moan filled the Zuiva’s small cabin. A few paragraphs later, the danger was spelled out clearly: “An adult might be very ill from the sting, but a baby could easily die from the poison. First, they knew, would come swelling and fever and tightened throat, and then cramps in the stomach, and then Coyotito might die if enough of the poison had gone in.”

I looked up to see Aryeh and Tziporah’s expressions. Both of them looked a little queasy, with parted lips and wrinkled brows. But that was not the end of the story. The baby was treated quickly and did not die from the scorpion sting. Which was lucky for us and our delicate audience. We all could exhale.

In Guaymas, there was an elegant, old-fashioned resort, the Hotel Cortez. Brian and I had stayed there six years earlier, when I was pregnant with Aryeh. It had been our first taste of the gulf after weeks of tramping around inland Mexico. We had woken next to the blue sea, invigorated by the clear morning air and boundless horizon. We had been served breakfast in an ornate dining room facing the gulf. Scooping the last spoonfuls of melon into our mouths, we had spotted dolphins through the restaurant’s French doors. It had been a magical moment, during which my first-trimester nausea had lifted and cleared, if only briefly. We’d always dreamed of returning.

|

| Aryeh draws in his sketch book. |

|

Of course, we were flat broke this time around. But no matter: during our first stay, the hotel (which also hosted RVs) had allowed us to pitch a tent in their extensive parking lot. We had been able to sleep cheaply while enjoying the hotel’s fine dining, showers, and pool. That’s one reason we loved the place.

We remembered the dolphins and the view, but not the hotel’s exact location or even its name. We spent hours searching, certain only that the Hotel Cortez was sequestered away from town, off a dirt road, behind an immense screen of palm trees. At every dead-end we reassured the children that we were on the trail to paradise. Once we located this phantom hotel, we promised, all pleasures would follow: food and plumbing and the best view in Mexico. When we finally arrived, around 9 p.m., Aryeh and Tziporah were woozy with hunger and exhaustion, but Brian and I were triumphant. We babbled to the night guard. (“Years ago, before the children...”) We paused in the parking lot, paralyzed by our wistful memories. (“The bougainvillea -- do you remember?”) Finally, we charged toward the front desk (“You check us in and I’ll see if the restaurant is still open — I can’t wait to see the view in the morning!”)

But then nostalgia met its demise, shattered like a clay-pot piñata. The front-desk lady would not allow us to pitch our tent in the RV lot. We told her about our previous stay, but the romantic simplicity of it did not impress her. Even though the parking lot was empty, even though ancient bellhops haunted the hotel’s dark hallways in desperate search of some suitcase to lift, she would not cut us a deal. We shrugged in defeat and asked about regular rooms. But this, too, had changed—the rates were much higher than any we remembered. Time had passed; the dollar had weakened. In any case, we could not afford to stay.

“What do we do now?” Brian asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I can’t think. Let’s go outside.” The front-desk lady, and all the bellhops too, looked relieved to see us go.

Beyond the grand hotel’s front doors, on the way to the parking lot, we passed a fountain. A warm, soothing wind blew. A soft light illuminated our path. We could smell the bougainvillea. The moon, a pale orb above us, worked its tidal magic on the sparkling gulf.

“Here,” I said. “Perfect. Let’s sit. The kids can play while we compare our options.”

|

| This sea star is one of about 2,000 invertebrate species that drew John Steinbeck - and later, the Lax Family - to Mexico's Sea of Cortez. |

|

Aryeh chased Tziporah around the bubbling fountain for a minute or so, until the strap on his sandal broke. “See? I need a new pair,” he griped. But Brian and I were already crunching numbers -- how much credit we had left on our Visa, how much a typical Guaymas motel might cost. We did not want to discuss shoe shopping.

“Just take the sandal off and keep playing,” I said. “The concrete’s fine. We’re not tidepooling.”

He shrugged and removed the sandal. Brian and I returned to arithmetic. “Even if we can find a cheaper place, I just don’t want to drive anymore. And to find a good camping beach this late...”

That’s when Aryeh shrieked. His mouth formed a great gaping hole. Sound gushed forth -- a primal banshee wail.

Aryeh’s scream seemed never-ending, but it was really time that slowed down. I stared at him. He was balanced on one foot, with mouth still agape. Then my eyes tracked to the concrete walk around the fountain. And there on the well-lit walk was the thing: honey-colored body, arched tail, pincers brandished, every arthropod segment glowing. I hold that image in my mind even now, framed by horror, and perhaps I have embellished it, just as I have reviewed a dozen times the steps that led to the moment. (Financial distraction, broken sandal, my own bad advice, and then that evil thing....) At some point, Brian ran to Aryeh and scooped him up, and Tziporah found her way into my arms. And at some point, too, Brian had the sense to run after the scorpion and get a good look at it, to try to identify its species and estimate its toxicity, though — to my regret — he did not kill it.

Then, somehow, Tziporah was in Brian’s arms and Aryeh was in mine, yelling about his foot, and we were hurrying into the same hotel lobby we’d just departed. The front desk lady rolled her eyes and the bellhop looked away, as if embarrassed to watch us petition again about camping options or a discount. But I shouted at them both, “We’re not here for a room. It’s my son. Un alacrán. From out there, by the fountain. He’s really hurt. You have to help us!”

All cynicism drained from the woman’s face. She shuffled behind the desk and produced a white pill -- an antihistamine, we were later told. I should have cared more about medical specifics—what dosage was this, and would it even help—but I was too distraught to think clearly. “Swallow,” I ordered Aryeh.

The bellhop vanished and reappeared with several garlic cloves, a folk remedy. We made Aryeh chew the garlic, though he cried while he did so, the pungent pieces a sobby mush in his half-open mouth. Tears splashed down his cheek. The garlic made him gag. He said he might throw up. I begged someone to bring a glass of milk, and after a few minutes, one appeared. We propped him on a lobby couch, swollen foot stabilized on a pillow.

|

| Andromeda and Aryeh paddle a kayak. |

|

“Is it okay?” I asked Aryeh. “How do you feel?”

“It’s in my leg now. All the way to here,” he said, voice shaking, while he pointed to his groin. “It kinda hurts. But it’s numb, too.” And this was worse than pain, because we knew that the numbness meant the poison was traveling toward his heart, and was already halfway there.

I begged the front-desk lady to call a doctor, the paramedics, anyone. “You have to help us!”

Aryeh looked to Brian. “It was a small one, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” Brian said. “The small kind.”

Aryeh knew too much. He knew the most dangerous scorpions are the little ones, not the more visually frightening larger kind. He knew that adults aren’t really endangered by scorpion stings, but that babies and young children under 30 pounds sometimes die. Aryeh weighed about 38 pounds. He remembered The Pearl, of course. We all did. And he couldn’t feel his leg.

“Keep chewing,” I told him while the bellhop rubbed his toe with a garlic clove. “Crackers? Anyone have crackers?”

Meanwhile, the bellhop mused nonchalantly in Spanish to the front-desk lady, “I’ve seen it many times. Children die. I wouldn’t be surprised.”

|

|

|