|

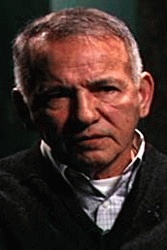

Emil Notti, former commissioner for the Alaska Department of Community and Regional Affairs, has held many positions including president of the Alaska Federation of Natives, senior vice-president of Doyon Limited, and deputy commissioner for the Department of Health and Social Services. Notti was a key participant in the negotiations that culminated in the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act.

Sharon McConnell: What were you doing during the years before and after the Claims Act was passed?

|

| Emil Notti |

|

Emil Notti: I was an electronics engineer working on test equipment for the guidance system on the Minute Man Missile in Los Angeles. I came back to Alaska and went to work for the FAA as an electronics engineer. I got interested in what was happening with Native people so I worked for the state's Human Rights Commission. I was there when I started devoting time to Native issues. I slowly got pulled deeper and deeper until, finally, I was doing it full time.

Sharon McConnell: What motivated you to be involved in Native issues?

Emil Notti: Nick Gray inspired me to take an interest. We were interested in housing, which was extremely bad, and education achievement was low. Hill statistics were terrible. The average age of death for Alaska Natives was 34 years old. Infant mortality was three times the national average. The worst tuberculosis epidemic ever recorded occurred among the Native people. Jobs for Native people were very hard to come by; very few people were working. We were working on a whole host of social issues. When we came across the land claims issue, Nick Gray and Howard Rock were very prominent, and we started dealing with some of these issues.

Sharon McConnell: Can you tell me a little bit about those first few years after the Claims Act was passed? What was the atmosphere like?

Emil Notti: There was a lot of expectation. A lot of people in the non-Native community were afraid of land claims; they thought they'd be excluded from vast areas of Alaska, and they wouldn't be able to hunt like they liked to. We were very busy trying to get the Native corporations up and running. The corporations had a lot of issues like, believe it or not, easements along waterways. Rights-of-way were a big issue, and they still are today, 30 years later. The state of Alaska is going to start asserting they have the right to cross the lands. The state identified several thousand rights-of-way, 600 or so qualified, and they're trying to get 200 or more established as so they have a right to go on land without compensating its owners. The corporations were faced with a lot of those issues. It wasn't until a few years later that we started learning how to manage investments and start subsidiary companies and move into the business world.

Sharon McConnell: What were those early years like with AFN? We've heard a lot of stories about you and about the nine dollars. Can you just tell us what it was like back then?

Emil Notti: Today it's hard to imagine that we didn't have the lawyers, accountants, or advisors that we needed. Back then we had to rely upon ourselves. Luckily, we had people like Willie Hensley and John Borbridge who were very articulate. When we started AFN, it was hard because we did not know each other. When I wrote that first letter to call people to the statewide meeting, I envisioned 14 people showing up, half of whom I wouldn't know. But every week, from July until October, we had 300 people show up. It was exciting, but we didn't know each other. It was hard to get people to start trusting each other. We would hold meetings from eight o'clock in the morning until 10, 11 o'clock at night. They were wide open; everybody had a say. We would vote on issues, it was hard to get everybody to work towards consensus.

With these open meetings, people started trusting each other; they all had a say and they were all treated with respect. Even if we had great differences of opinion, we arrived at a position, issue by issue -- the amount of land, the amount of money. The land was a big issue, because it ended up there were two formulas—one based on population, one based on area lost by your tribe -- and those things were hammered out with great emotion and conviction. After a lot of arguments and discussion, we arrived at our positions and marched on to Congress.

Then we worked with the state government, trying to get them to support our positions. We worked with the federal agencies. Most of them did not agree with us. Very few people agreed with us, as a matter of fact. It took a great effort to convince Congress and the administration. Laura Bergt set up a meeting between Vice President Agnew and Don Wright. Don Wright, I'm told, made the greatest presentation justifying 40 million acres of land. Agnew agreed to it, and that became the president's position. A lot of people were involved at the right time—they had the right words and they made the right phone calls to make it happen. We were going around the country talking to as many support groups as we could. Willie Hensley was on "Good Morning, America." I went to Detroit in Cobo Hall and talked to the National Council of Churches. Ten thousand ministers were in the audience. We got a unanimous resolution backing our position on land claims. We got the AFL-CIO. We had a hard time before the Senate and House because there were some skeptics who didn't quite agree with what we were doing. I remember, the first time I sat down, we finally got lawyers to support us. The first time I sat down before a Senate committee —Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg was on one side and Attorney General for the United States Ramsey Clark was on the other—and the whole atmosphere changed. All of a sudden they started taking us much more seriously. Everything came together step by step. When you look at it, it was a major accomplishment.

Sharon McConnell: What was the promise of ANCSA 30 years ago and has it fulfilled its promise?

Emil Notti: It's hard to say, because a lot of things we're trying to measure are not measurable. When we started out, very few of us knew anything about corporations. One of our goals was to get Native people involved in the economic system so that as Alaska grew, they wouldn't be left out. There we were, in 1940, with 72,000 people. Today we have over 600,000 people, and a whole new economic system. People are learning to participate, not just as workers but as managers. It's hard to measure the confidence that people have now—they have their own corporations, they can deal with bankers and accountants, and they are becoming bankers, accountants and lawyers themselves. I think these things are part of the accomplishments of Land Claims. Native people are no longer trying to work for corporations, but instead, are becoming owners of corporations.

Sharon McConnell: What about some of the developments that no one foresaw? What were some of the unintended consequences ANCSA? For example, and I hate that term, but it's been referred to as "After-Borns." That wasn't something that people foresaw.

Emil Notti: That was one of the oversights. Looking back, it probably would have been better to include people born after 1971, as long as they met the criteria to become full members of the corporations.

Sharon McConnell: How do you think the Claims Act changed Alaskans, particularly Alaskan Natives?

Emil Notti: One of the things we wanted to do was make sure that people participated. It changed the Native people, because Native people had to change. We had no choice in that issue. As the population of Alaska grows, we're going to have a million Native people and so we'll become a much smaller minority in the state. We have learned to function in the economy and we'll have to continue to do so. We still have 80 percent unemployment in many of the villages. We need to get the employment up in those villages. We have people flying in and out of the state, two weeks on, two weeks off. We need to get the villagers to fly on and off the job, one week on, one week off, two weeks on, two weeks off. When that happens, when our unemployment rate approaches the averages of the rest of the state, I think we can start feeling we've accomplished one of the major goals of Land Claims.

Sharon McConnell: What do you think the next 30 years are going to be like? What do you think we're going to be facing?

Emil Notti: Thirty years from now, we'll still be talking about subsistence. Maybe we'll have settled the sovereignty issue in the courts. Sovereignty is the wrong word. We're not talking about sovereignty, we're talking about limited self-rule, about having more to say about what happens in our lives, about not being dictated to by a government that's distant from us. We've come a long way by creating corporations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs no longer makes decisions for us and oversees what we do.

Sharon McConnell: What is one of your most vivid ANCSA memories?

Emil Notti: One of the big events after the struggle of trying to get Congress to recognize our rights was the night we stood and listened to President Nixon say he signed the bill into law. That was a big moment in our effort to get a land settlement.

Sharon McConnell: What was going through your mind when that happened?

Emil Notti: Well, we had no illusions. We knew we had a lot of work to do and, the signing just meant that we needed to shift gears and look inward.

Sharon McConnell: But ANCSA's changed your life a lot because you were so involved before and after. You're one of our Native leaders and very well known in the state of Alaska. What has that meant to you?

Emil Notti: It did bring me a lot of notoriety because I was involved with every issue that came up. I wasn't so involved after the settlement. I stepped away and have been doing more things for myself than I did during that time. During that effort I had very little free time at all. My phone was ringing all hours of the night and day and I did a lot of traveling. Afterwards, I just stepped back.

|