|

In 1908, hopeful miners throughout Alaska and the Yukon flooded the Iditarod region following the discovery of gold on Otter Creek. Within a year the main camp in the gold fields developed at Flat. A second discovery attracted a new wave of arrivals and resulted in the birth of boomtown Iditarod, complete with hotels and restaurants, newspapers, a bank, and brothels. In the town's prime, automobiles motored along the streets and a well-appointed courthouse handled legal matters of the district.

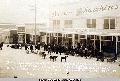

In summer months, many people and supplies came in on steamers and barges via the Yukon, Innoko, and Iditarod Rivers. Overland, a network of trails crisscrossed the backcountry, linking Flat, Discovery, Otter, Dikeman, and Willow Creek with outlying villages. On the main Iditarod Trail and other connecting trails, one could travel all the way to Nome or southeast to the port of Seward. The 900 miles between Seward and Nome were mapped as early as 1908. Freight, mail, and gold moved through the country via dogsled team.

Traveling the Iditarod was no easy ride, but it was a worthwhile journey, said C. K. Snow, a member of the territory's House of Representatives from 1915-1918. Hailing from Ruby, Snow represented the voters of the 4th District. On February 15, 1919, standing at one end of the trail in Seward, Snow offered this perspective: "If you love the grandeur of nature -- its canyons, its mountains and its mightiness, and love to feel the thrill of their presence -- then take the trip by all means; you will not be disappointed. But if you wish to travel on ‘flowery beds of ease' and wish to snooze and dream that you are a special product of higher civilization too finely adjusted for this more strenuous life, then don't. But may God pity you, for you will lose one thing worth living for if you have the opportunity to make this trip and fail to do so."

Around Iditarod, the easiest gold was gone by 1930, and with the decline, miners, bankers, and businesspeople moved on to other locales. Some buildings were moved to Flat; others decayed with time. Iditarod was a ghost town when Anchorage was still young. Airplanes had replaced dog teams for carrying mail and freight. In many villages, snowmobiles began taking the place of dog teams for hauling people, water, and wood. The Iditarod Trail saw less use.

In 1967, as Alaska was celebrating the 100th anniversary of the U.S. purchase from Russia, the old Iditarod Trail came to light again. A Wasilla woman named Dorothy Page promoted the idea of cleaning up a portion of the disused trail and staging a two-day race of 25 miles a day. Knik homesteader Joe Redington, Sr., and other local mushers and pioneers helped with fundraising and brushing out the trail. Six years later, Page threw her support behind Redington when he had a notion to revive the race idea, but extend it all the way to Nome. Page, who died in 1989, is remembered as the "Mother of the Iditarod" for her work on that precursor to the famous long-distance race of today.

Redington had mushed dogs for the U.S. Army in search, rescue, and recovery operations and was saddened at the changes he'd witnessed in Bush Alaska, seeing more snowmachines and fewer dog teams. A portion of the Iditarod Trail passed near his homestead, and he had personally kept it brushed out to run his dogs. He'd also seen the enthusiastic response to the Centennial Race in 1967. So in 1972 and early 1973, Redington stumped for the idea of a longer sled dog race to demonstrate the superiority of Alaska sled dogs.

Although Redington had first proposed a 500-mile race to the ghost town of Iditarod, musher Dick Mackey upped the ante and suggested they go all the way to Nome, more than a thousand miles. Decades later, Mackey remembered the scene at the first starting line in 1973:

"Half the family was there," he said, "but the mothers and daughters and so forth were all crying. It was tough on them because they thought they're never going to see you again . . . you're going off in the middle of nowhere. And I suspect a great many of us wondered if, in fact, we would make it."

They did make it, even though the last musher crossed the finish line 32 days after leaving Anchorage. The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race has been staged every year since then, attracting teams from all over the world, and Redington is remembered as the "Father of the Iditarod."

In 1977, recognizing the historical importance of the route in the territory's development, Alaska's U.S. Senator Mike Gravel proposed naming the Iditarod as the nation's first "Historic Trail." A year later, President James Carter signed the National Historic Trail Bill. The Iditarod's designation was followed by other trails with great historic significance: Oregon, Mormon, Pioneer, Lewis & Clark, Over Mountain, Victory, Nez Perce, Santa Fe, Trail of Tears, Juan Bautista, and the Pony Express.

Upkeep of the Iditarod National Historic Trail is complicated because, from Seward to Nome, it crosses lands that are private and Native-owned, or public lands that are managed by various agencies. The Bureau of Land Management now administers the 2,200 miles of winter trails affiliated with the National Historic Trail. Through the nonprofit organization, Iditarod National Historic Trail, Inc., various "Trail Blazer" clubs in trail communities count on volunteer laborers and federal grant funding to help keep their portion of trail open and well-marked.

In the modern Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, the ghost town of Iditarod is a halfway checkpoint stop for mushers following the southern route, which is run during odd-numbered years. Little evidence of a bustling gold-rush town remains. There are no buildings to house volunteers or welcome the mushers, so they operate out of tents erected solely for the race.

The name Iditarod, a long-dead town on a remote Alaskan river, has achieved international fame thanks to mushers who, like territorial Rep. C. K. Snow, do not wish to travel on "flowery beds of ease."

|

|

|

| Z. J. Loussac (left) pausing on trail |

|

|

|

|

| Dog teams moved mail and freight over trails |

|

|

|

|

| A team on the trail connecting Seward to Anchorage |

|

|

|

|

| Team fresh from the Iditarod goldfields |

|

|

|

|

| Gold bricks worth $125,000 |

|

|

|

| Click here for all 10 photos in this gallery. |

|