|

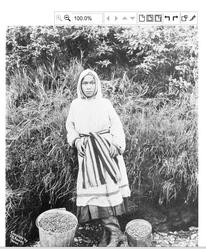

| Women and children with pails of berries |

|

The men of my grandfather's family, the Ugiuvangmiut (people of Ugiuvak) from King Island, would hunt bearded seal, walrus, polar bears, and hair seal. They would climb straight up the vertical cliffs of the island to find the eggs of murres and other nesting sea birds. Elders, women, and children would fish through the shore ice that girded the island in the winter and go crabbing as well. In the late spring and early summer, after the season of hunting sea mammals came to a close, King Island families would prepare to visit the mainland of the Seward Peninsula to gather greens, net and dry salmon, and collect berries near my grandmother's family, the Kauweramiut (people of Kauwerak), to cargo back to King Island by the ton.

Although one of the unique features of King Island is qaitquq (the cave) -- a natural opening deep into the permafrost of the island, in which the island's sizeable population would store food during times of plenty -- our ancestors lived in a world of feast or famine. Despite masterful skill as hunters and expertise with seasonal harvests, Alaska Native people survived in an unforgiving and unpredictable environment. Roger Silook, a St. Lawrence Island Yupik man from Gambell, underscores the urgency of food shortages and hunger in his story, "A Time of Starvation":

"Many days the men never hunt because of storm and wrong wind direction. When that happens their food gets low; even some people run out of food and begin starving. They have no stores then to get food so they just live day after day without food and finally they start to eat some of their skin ropes or pieces out of their skin houses."

In an effort to prevent times of starvation like those described by Mr. Silook, the territorial government began to establish reindeer farms in Northwest Alaska. The success of the "reindeer queen," Mary Antisarlook, who eventually held the largest herd of reindeer in the Arctic, is well-known. To this day, reindeer -- descendants of the reindeer that became feral after their Inupiaq herding families were killed in the 1918 influenza pandemic -- continue to thrive in the region, alongside migrating caribou. Until the flu orphaned my grandmother and her two sisters, my grandmother's family from Kauwerak also worked as reindeer herders, trading meat and hides for other provisions.

Like the villages of my Kauweramiut and Ugiuvangmiut ancestors, traditional community sites are places of strategic access to resources, including food. Over the course of thousands of years, Alaska Native people have developed knowledge of seasonal plant habitats and animal migrations. Alaska can be a land of tremendous abundance: berries, greens, and seaweed as well as fish, caribou, oysters and clams, moose, bear, whales and other sea mammals, waterfowl or small game such as hares and ptarmigan. Food nourishes more than the body; our families and communities connect more strongly within and to each other because of food. Children learn to invest meaning in the rituals of sharing, gifting and exchanging food. In times of prosperity and hardship alike, relationships grow and change as communities trade food with each other and distribute food. Feasts commemorate and bring people together.

It would be compelling to focus solely on the consumption of food, enjoying the texture and rich flavor of half-dried salmon, the vivid ruby hues of frozen cranberries and currants, the evocative and bitter tang of suraq -- young shoots of willow -- balanced by the buttery seal oil it is stored in. But to do so would leave aside the discussion of acquiring food, of processing it and storing it: eating in the arctic and subarctic is only one part of the highly adapted and highly skilled process of subsisting and passing along values and traditions. The complex ecology that brings about such an abundant and rich source of food is one that Alaska Native people have observed and adjusted to over generations and fluctuations of climate and other natural cycles.

|

| Walrus hunters take a break to eat lunch |

|

Focusing on the movement of food to people and people to food and all the steps involved would also ignore the cultural, spiritual, and inherently personal role of sustenance. Subsistence is commonly called the "subsistence way of life" because it isn't simply a political issue, a social function, or a matter of nutrition. As Margie Brown says of the Alaska Native rights movement, one of the main issues that unite indigenous people in communities across the state is providing food for families. She notes that Alaska Native rights have to do with the "the right to hunt, fish, trap, and subsist; to use the resources of the land. Alaska Natives' ties to the land, unlike in the Lower 48, have never really been broken, and that is a key issue for Alaska Natives." In this way, food is joined with land, and with the basic needs that drive people to seek rights, historically and fundamentally. Rex Rock, Sr., Inupiaq of Point Hope, says that whaling relates to those needs:

"Our culture's real rich as far as whaling goes. There's so much respect for the bowhead whale. Basically, that's what our community's based around. What I've learned -- what I grew up with and maintained -- is sharing. You don't get the whale. It comes to you. That's what I've been taught."

Food is also joined with one's first experiences. In a Harper's Magazine article written after a trip to the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, Rowan Jacobson recounts the importance of king salmon to the first memories of young children:

"The Yupik have a word, slungak, that translates as 'coming to.' It describes when awareness first blossoms in a child, when the child stops living purely in the moment and becomes conscious of time and place and self and starts to lay down memories. For many Yupik, slungak kicks in when the kings run."

Accordingly, throughout Alaska, boys learn to hunt and treat the animals they harvest with respect. Girls follow their mothers and other women to gather blueberries, salmonberries, cranberries, and greens such as sourdock, saxifrage, and wild celery and distinguish these beneficial plants from poisonous and medicinal one. An essay written by Fallon Fairbanks, an 11-year old Inupiaq girl from Kotzebue, details the continuing importance of collecting, sharing, and learning about food from netting herring to picking berries:

|

| Young girl with berries |

|

"At the end of July, into August, we are just finishing our fish and starting to pick berries. There are various types of berries where I live. Some of them that we pick are blueberries, blackberries, cranberries and ugpichs (uk-picks), also known as salmonberries because they are orange with lots of seeds and look like salmon eggs."

Just as many of the Inupiaq words in my vocabulary describe niqipaq (food), many of my most compelling recollections about nourishment come from traditional food: paniqtuq (dried seal meat), aluk (blackberries), angimaaq (boiled half-dried salmon) and those who shared this food with me. As a mother, I am relearning that children begin to build an understanding of the world and themselves by naming the things that they know. Talking about food and its origins ensures that our children will grow in a world that maintains a diversity of language and life as long as our food continues to be diverse and respected.

Related links:

Alaska Traditional Knowledge and Native Foods Database:

http://www.nativeknowledge.org/

Fallon Fairbanks essay:

http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=Peer%20Work&page=Nonfiction&ContentId=1490&viewpost=2

Sinrock Mary:

http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=Digital-Archives&page=People-of-the-North&cat=Native-Lives-and-Traditions&viewpost=2&ContentId=2564

Rex Allen Rock, Sr. interview:

http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=History%20and%20Culture&page=ANCSA%20at%2030&cat=Interviews&ContentId=848&viewpost=2&pg=101&crt=1

Roger Silook stories:

http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=History%20and%20Culture&page=Art%20of%20Storytelling&ContentId=837&viewpost=2

|

|

|