|

|

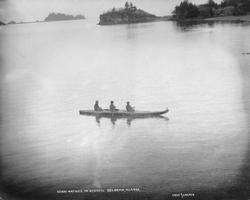

| Three men travel in an Alutiiq baidarka |

|

In the Inupiaq language, words for travel refer to the landscape: moving upriver, downriver, away from shore, with the wind. The western conception of travel bases itself on battling with the elements and conquering landscape. In English, travel's etymological roots trace back to trouble -- suffering and painful effort. Noting these fundamental linguistic differences may be over-determined, but differences -- in the technologies employed in covering distances, moving between places, and the languages used to describe them -- present themselves. Even the idea of technology related to travel is questionable: a kayak is not simply a product or an output. It's a part of departure and return -- of the hunter who uses the kayak to travel in search of food, as well as of the seals whose skins cover the kayak itself, and the community fed by the harvest of the hunter that in turn records and transmits the story of the hunter and his travels.

In many ways -- both in the way of thinking and in the actual way of undertaking of transportation -- Alaska Native travel makes use of the natural features of the land rather than perceiving the landscape as an obstacle or a desolate wilderness to be passed through without incident. Alaska's indigenous people continue to create and use the methods of travel that our ancestors have developed and refined over millennia. When practical, we adopt Western innovations, but for the most part we work within tradition. Aluminum skiffs, ready-made, may not require as much initial labor as umiat (skin boats), but their metallic sounds interfere with hunting. They also preclude safest passage through choppy waters and arrival on boulder beaches.

At the height of the industrial era, nearly unthinkable ways of moving through the country abounded as non-Native people arrived in Alaska by steamship and rail at great expense and risk. Accounts include one man attempting to bicycle to Nome during the Alaskan gold rush, as well as numerous stories of mishaps and losses of ships and their crews up and down the margins of the land and sea. To this day, train trestles constructed by my grandfather and his generation on the Seward Peninsula still stand, although the mines to which the train tracks led have long since been abandoned; "the last train to nowhere" remains stranded on the tundra between Council and Solomon, rusting away.

Just as these markers of transport suggest the misapplication and futility of industrialization in the arctic, traditional means of transport underscore true knowledge of the land. Indigenous modes of transportation successfully use natural materials -- skins of large land and sea mammals, trees harvested from the dense forests along with the well-weathered driftwood washed up along treeless coasts, ivory -- that thrive in and among the elements of the landscape that Alaska Native people depend upon for subsistence and inhabitation.

|

| Travelers in umiak loaded with cargo |

|

Traditional materials -- ugruk (bearded walrus) hides for boat skin coverings, sinew for lashings -- imply utility and resourcefulness. They also point to traditional knowledge and its bottom line. One who has learned how to construct a traditional walrus-skin boat is more likely to have acquired knowledge of navigating known dangers: the currents and channels at sea. In this way, adaptation does not reside solely in technology as result or end; it resides in the transmission, accumulation, and application of collective knowledge.

Dr. Dolly Garza, who is of Tlingit and Haida descent, prefaces her retelling of the story, "Tlingit Moon and Tide," noting that it is not simply a matter of knowing the earth under your feet or the waters beneath the hull of your boat that make your travels safe, but also knowledge of the moon:

"Native peoples depend on the low tides to harvest beaches packed with shellfish and seaweeds. We are aware of the ebb and flow of the waters and how that can impact safe water travel. We are aware of the relationship between the moon and the tide."

On the other hand, stories about the dangers of travel show that those who don't possess knowledge of their environments make themselves especially vulnerable. Ada Blackjack was an Inupiaq woman who was hired to accompany five non-Native men as they tried to colonize remote Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean. Blackjack was stranded on Wrangel Island after ice prevented rescue by boat and the party she initially traveled with departed the island on dogsled over the winter ice pack. She wrote of her hopes to be rescued:

"They promised that they would come back after they got to Nome, with a ship, and if they couldn't get there with a ship they would come over with a dog team next winter. They left with a team of five dogs and a big sled of supplies."

After nearly two years of being away from home, Blackjack was brought back to mainland Alaska by a search party that was sent to rescue the men who originally accompanied her to the island.

|

| Musher outfitting dog with protective booties |

|

Alaska's terrain continues to render many urban and suburban vehicles useless -- cars, bicycles, and even airplanes prove impractical in many communities that thrived pre-contact and continue to thrive today. These vehicles succeed when their intended terrain is uniform and forced upon a landscape. That is, when asphalt is laid down or when roads are graded and maintained. Places such as Pelican, Hooper Bay, and Diomede host populations without roads, paved paths or sites suited to airstrips. These and other communities trace their origins to the basic strength of the land and its resources.

On navigable water, innovations abound. 60-foot dugout canoes carved from cottonwood as well as red and yellow cedar in the Southeast. Birch bark canoes for navigating Interior waterways. Large cargo boats constructed of walrus hides, capable of ferrying several tons of cargo and loads of 20 or more people. Kayaks built from walrus hides, even in their compact size capable of withstanding the strong currents and storm surges of the North Pacific, the Bering Sea, and the Gulf of Alaska.

In the winter, the same bodies of water prove navigable in other ways. On ice and snow, dog sleds for traveling along flat tidal areas and up and down rivers. Snowshoes to equip lone travelers to make good time over difficult terrain, including countless ponds, streams, and through considerable elevation gains.

As with most adaptations, these means of transport are born from resourcefulness, necessity, and knowledge. Whether collective or individual, cyclical or unanticipated, the reasons for undertaking journeys are as complex as the terrain traversed. Often faring through environments that require precise knowledge of currents, elevation features, and ice conditions, Alaska Native people historically base trips on developing trade networks, seeking and securing food sources, relocating according to favorable and unfavorable seasonal and climactic variations, advancing existing relationships and initiating new ones, performing ceremonies of ritual significance, or turning to evasive travel when politics or resource scarcity made movement the best course of action to sustain life. As in the poem "Sikuliqiruq: The Ice is Breaking Up and Moving ," by LaVon Bridges:

Sikuliqiruq,

The ice is breaking up.

Sikuliqiruq,

The ice is breaking up.

Moving, moving.

Sikuliqiruq,

Moving, moving.

Sikuliqiruq.

Related Links:

Ada Blackjack:

http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=History-and-Culture&page=Life-in-Alaska&viewpost=2&ContentId=850

Dr. Dolly Garza - The Origins of Moon And Tide:

http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=History-and-Culture&page=Art-of-Storytelling&viewpost=2&contentid=845

LaVon Bridges:

http://www.litsite.org/index.cfm?section=Teaching%20and%20Learning&page=Reading%20Workbooks&cat=Elementary%20School&ContentId=1070&viewpost=2&pg=185&crt=1

|

|

|