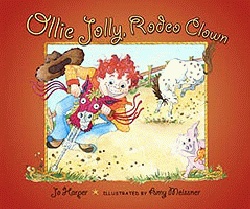

My husband owns a pair of iguana-skinned cowboy boots that were hand-me-downs from his Grandpa Charlie. They were brand new when he acquired them, when Grandpa decided he “wasn’t too sure about that iguana” and his new wife thought dimpled gray ostrich skin would suit him better anyway. The boot toes are curled now, the nails inching from the soles, and my husband never wears them anymore because they kill his back. But I tripped over these boots everyday in my studio when I began the illustrations for Ollie Jolly, Rodeo Clown, a picture storybook written by Jo Harper -- Jo Harper, from Texas. Someone from Texas, who writes a book about cowboys, obviously knows about cowboy boots, iguana or dimpled ostrich.

If somebody illustrates a book about cowboys, well, she’d better know boots too. And she’d better know the landscape

|

| Ollie Jolly Cover |

|

I did live in the Nevada desert for twelve years -- and I hated it. I moved there when I was ten years old, from lush acreage in California where my sister and I had so many tree forts and knotted rope swings that we lost count. There are very few sagebrush in Nevada that are big enough to become a tree fort or support a swing, which is not to say we didn’t try, but many of our schematic designs were far from realized. We’d run screaming into the house after uncovering a dead scorpion or hearing a coyote yip in the hills. In California, the scariest thing in the bushes was poison oak, and that was nothing a little Calamine lotion couldn’t cure. But Nevada brush was dusty and gray, a hidden cicada could just as easily be a snake’s rattle. The wind blew eighty miles an hour on a good day, and as I became a teenager, Nevada became “boring” and I rebelled against everything there -- including the thought of being a cowboy or wearing dusty boots.

Now, in Alaska and eight years removed from desert life, I was being asked to create a cowboy landscape for a children’s book. It was for practical reasons, initially, that I started missing the desert. It just wasn’t right outside the window for handy reference or quick inspiration. I had to remember colors, textures, layers, smells, and most importantly, recreate the desert in my mind -- a desert that would actually feel good to remember. I started with the iguana boots.

Sometimes I held a boot in my lap while I sketched the other; sometimes I memorized the stitching patterns on the sole or did gesture drawings of a three-quarter view of a boot suspended in mid-air; sometimes they just leaned in the corner behind me. At first, they were a constant reminder of my responsibility to the author and to the audience, of my fear that I wasn’t going to be able to illustrate an entire book when I couldn’t even draw a boot properly; ultimately, I thought everyone would know that the desert wasn’t something that I loved. If they knew this, then they would think I was some kind of a fraud, a hack. When I walked into my studio each morning and saw the boots slouched on the floor, my stomach would flutter: I wasn’t going to get it right, any of it.

But somewhere in the process -- maybe on the day I learned how to really draw a boot -- this dark critic slunk away and the task became less about getting it to look right, and more about getting it to feel right. That was better. I knew I could create a painting that felt good to look at.

I hung a string of plastic cactus lights above my desk so I could imagine I was somewhere warm and dusty, while the Alaskan snow bank slowly rose outside my window in mid-January -- I could imagine Texas. Of course, I had to take the lights down because the cat began using my drafting table as a springboard to reach them, and my husband was convinced that I was going to burn the house down when I forgot to unplug them. So I hung horse and cowboy photocopies on my bulletin board instead and started listening to country music on the radio as I worked.

There was a part of me that understood that I had to create a sort of scaffolding -- a skeleton -- something strong enough to support these layers of narrative, this story other than my own that I had to tell. This went beyond research and I allowed myself to build a fictional world, a repository where I could pull details from a false recollection. This is how I existed, holed up like an oblivious tarantula in a terrarium, for the many months this project lasted. I created an alternate set of memories for myself by creating a fictional space to move through, work in, and look at.

Maybe it happened while I was wandering around in my husband’s boots, seeing if I, too, could stand like a cowboy in front of the mirror -- I lost that desert childhood disappointment and boredom. In the end, I don’t think the illustrations for Ollie Jolly, Rodeo Clown reveal how I used to feel about the desert. They reveal how I feel now.

If I found a dead scorpion under a board tomorrow, I wouldn’t run away screaming; I’d take it home and thumbtack it to my bulletin board. It would be good to look at.

Images courtesy of WestWinds Press®, an Imprint of Graphic Arts Publishing Company