|

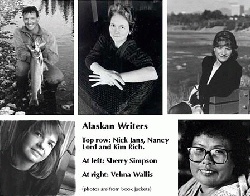

| Five Alaskan Writers |

|

Ten years ago, Sue Henry was better known as a grant writer than as a mystery writer. The former education administrator had just about given up waiting for an answer from Atlantic Monthly Press when, in January 1990, it finally accepted her first fiction manuscript,

Murder on the Iditarod Trail.

Fellow mystery maven Dana Stabenow was just as unknown. She had started the new decade as a struggling science fiction writer about to switch to mysteries. Her Edgar Award-winning A Cold Day for Murder was published in 1992.

Ten years ago, Nick Jans was a little-known schoolteacher in Ambler. Velma Wallis was living the quiet, unpublished life in Fort Yukon. John Straley, Sherry Simpson, Nancy Lord -- all of them welcomed the 1990s as mostly undiscovered or apprentice wordsmiths.

Alaska writers weren't the only ones struggling. A decade ago, publisher Kent Sturgis moved his fledgling company, Epicenter Press, from Fairbanks to Seattle.

"There was no infrastructure within the state -- (few) book editors or book illustrators, no one primarily printing books," he said.

If you've visited a bookstore lately, you know how far Alaska writers -- and readers, their beneficiaries -- have come. Technology has removed many local publishing barriers and made even self-publishing a more respectable option. Outside publishers, always intrigued by Alaska, now cater regularly to the world's appetite for frontier tales.

There's been a decade-long explosion in the number of books by or about Alaskans, especially in the area of children's books, memoirs and mysteries. Cook Inlet Book Co., for example, carries more than 5,700 Alaskana titles; Amazon.com lists nearly 3,000.

There also has been an evolution in more subtle aspects of the business.

"In 1990, we had just begun to raise the bar in terms of quality of publishing," said Sara Juday, regional manager for Alaska Northwest Books. "Before, we published books like Honeybuckets on the Kuskokwim. It was a cute little book, but not the same quality as books we've been doing since."

"Books in the past capitalized on the cliche of Alaska. Of course, it wasn't a cliche then. These were living stories, more like oral history. There was an innocence and sweetness to them. But I'm not sure there was a lot of depth."

Now Alaska writers are venturing into more challenging terrain: genre fiction with a more authentic bite and creative nonfiction that brings fiction's best storytelling tools to the "facts" of our northern existence. More writers and editors even live in our superlative state and write about -- should they dare? -- subjects other than Alaska.

The quality of books in all genres has improved dramatically, said Lynn Dixon, co-owner of Cook Inlet Book Co.

'There used to be an incredible amount of garbage. Now there are so many excellent books coming out, not only about people's connection to Alaska and philosophical ideas about why they're here, but also good books on history and Native culture. (These books) can stand up against any other books from any other state."

In fact, so many good books were published in the past 10 years that you might have missed a few. That's why we asked writers, booksellers and editors to recommend some notable books from the 1990s, to discuss the trends that helped fuel the Alaskana book boom and to note a few literary milestones passed along the way.

Million-Book Miracle

"A book about mushing? No kid in Alabama will want to read that," author Shelley Gill recalled a New York publisher saying to her back in the early 1980s.

Gill, a journalist and an Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race veteran, wanted to write a children's book about the famous dog race. East Coast publishers wouldn't bite. Gill, however, believed in the broad appeal, especially for children.

"I thought, what kid wouldn't be interested? I remember growing up in south Florida and reading about Jack London and drooling about wanting to come here."

Gill also considered her local audience -- she wanted Alaska kids to read about life in their own back yards. Children she'd encountered in the Bush had few choices in terms of reading material. Nearly all of it came from the Lower 48.

'These kids were all reading about subways and traffic," she said.

So Gill and a friend from Talkeetna, illustrator Shannon Cartwright, anted up. Gill mortgaged her home. Cartwright borrowed money. Together they launched PAWS IV, essentially a self-publishing operation based in Homer, and released Kiana's Iditarod in 1984. It was followed by a title each year on average.

Fast-forward to the 1990s: What Gill and Cartwright believed, the rest of the publishing world soon discovered: Children love reading about Alaska, and Alaskans frequently ship the books to friends and relatives Outside, especially during the holidays. Alaska Northwest Books jumped on the picture book bandwagon in 1992. A Child's Alaska, by Claire Rudolf Murphy and Charles Mason, was published in 1994 and became the company's top-selling children's book.

Now, shelves are crowded with imitators. And the biggest milestone for PAWS IV came in 1998. "We hit 1 million (books sold), and that's the last we bothered to count. We were getting tired," Gill said.

This year, Sasquatch Books in Seattle bought trade rights for the PAWS IV line of books, which now features 14 titles. The latest, Moose Racks, Bear Tracks, and Other Alaska Kid Snacks, a children's cookbook by Kodiak writer Alice Bugni and Cartwright, hit stores recently.

Gill and Cartwright continue to write and illustrate some of the books, but Gill also signed an 11-book contract with Charlesbridge, a Boston-area publisher that specializes in school activity guides.

"Everybody thinks it's easy," Gill cautions would-be children's book writers. "When they see something that works, everybody flocks to that idea."

She's not worried though. "I still have the good ideas six months to a year ahead of everyone else."

Hunger for Authentic Stories

If few people saw the kids' book boom coming, fewer expected a best seller to spring from the pen of Fort Yukon resident Velma Wallis. The Gwich'in writer's fictional tale about heroic survival, Two Old Women, might not have made it into print if Wallis' university classmates hadn't stood behind her, offering money to self-publish the book. In the end, that wasn't necessary.

"Initially, we didn't think of it as a commercial book," said Kent Sturgis at Epicenter Press. It wasn't necessarily a politically correct one, either.

Ignoring the criticism of at least one Native leader who thought the story made Athabaskans look bad, Epicenter published Two Old Women and immediately reaped the rewards. Wallis won the 1993 Western States Book Award for creative nonfiction. Reviewers lauded the book. Paperback rights sold to HarperCollins. At last count, Two Old Women has sold more than 500,000 copies in 17 languages. Movie rights have been optioned three times.

The story, which Wallis first heard from her mother, follows the struggles of two valiant elderly women who were abandoned by their people during a time of food scarcity. Cook Inlet Book Co. owner Dixon recalls, "I couldn't put it down. It was unpredictable, and it was not only about two women who got by, it was about two old, strong women -- which I'm getting to be."

"It hit a nerve on all sorts of levels," said Juday of Alaska Northwest Books. 'The fact that it was translated into so many languages demonstrates the incredible reach of that book."

Wallis was swept into a whirlwind of book tours. Her 1996 sequel, Bird Girl and the Man Who Followed the Sun, has sold only a fraction as many copies as the first, but she's still writing from her Fort Yukon home, and Epicenter Press is looking forward to publishing her next book, Sturgis said.

"She has been 100 percent successful weathering her fame. I find it just remarkable that the Velma Wallis of today is the same Velma Wallis we met five or six years ago."

The book was not only a wild ride for Wallis but a wild ride for Epicenter as well. By comparison, its second-best-selling book is Daily News columnist Mike Doogan's pocket-sized novelty How to Speak Alaskan, which has sold about 25,000 copies.

Profits from the Wallis book helped Epicenter grow from publishing three or four titles a year to 10 or 12 titles. In essence, Sturgis said, Two Old Women helped Epicenter publish other 'quieter' titles, among them Cold Starry Night by Claire Fejes and Ray Hudson's Aleutian memoir, Moments Rightly Placed.

Explosion of Creative Nonfiction

In turn, those books are part of another recent trend: memoirs with a strong sense of place, and other forms of creative nonfiction. Instead of the journalistic sweep of John McPhee's 1977 Coming Into the Country, Alaska readers of the 1990s were treated to more personal portraits of a dozen different landscapes and communities.

Among the notables were Natalie Kusz's Road Song, a bittersweet memoir that was as much about family life and adversity as it was about the frigid Interior. Sumner MacLeish's Seven Words for Wind captured the rhythms of Aleut life, including seal hunting, in the storm-tossed Pribilof Islands. Sherry Simpson's The Way Winter Comes spanned Alaska and featured "a journalist's objectivity combined with a poet's love of the word," according to one reviewer. It won the Chinook Literary Prize and a publishing deal with Sasquatch Books.

Almost all of these well-received nonfiction books were written by women, noted Ronald Spatz, director of the University of Alaska Anchorage Department of Creative Writing and Literary Arts. 'In Alaska, where women fish, hunt, work on pipelines and just about everything else, women also write, and they make a big difference in the literary community. They are, in fact, spreading a vision of place.'

That vision, he said, is more grounded in intimate details than exotic northern travels.

"I see these writers as modern explorers," Spatz said. 'They're documenting real life -- what's happening all over Alaska."

In this category, Spatz also named former Daily News reporter Kim Rich, who described the Anchorage underworld in her memoir Johnny's Girl; Leslie Leyland Fields, author of The Entangling Net: Alaska Commercial Fishing Women Tell Their Lives; and Homer writer Nancy Lord.

Why have so many of these books been written recently? For Lord, author of Fish Camp and Green Alaska (selected by Barnes & Noble Booksellers for its national series "Discover Great New Writers"), settling-in time was essential. Lord came to Alaska in 1973 and first made her mark as a writer of short fiction. She recalls reading an essay by former poet laureate John Haines, in which he claimed there was no genuine Alaska body of literature, and that it might take years -- even generations -- for one to develop.

"I thought, 'Oh my God, I'm not going to live that long,'" Lord said. "What can I possibly do, having not come into this country until so late?"

The Truth Is Not Good Enough

Lord began writing fiction because she felt she lacked the authority to write nonfiction, she said. But after 20 years in Alaska, she finally plunged into writing about life in a fish camp on the shore of Cook Inlet.

"I was late in making the realization that this was my natural material," she said.

'The truth is good enough up here. That's what we tell ourselves," said Nick Jans, who made his mark as an emerging nonfiction writer with his 1993 and 1996 essay collections, Last Light Breaking and A Place Beyond.

But Jans, who recently took a leave of absence from his Ambler teaching job to build a house in Juneau with his new wife, still hopes to pen the "great Alaska novel." Problem is, he said, the environment itself discourages novelists.

"Long fiction requires a real focus and dedication. Outside urban Alaska, everything pulls you away from writing, from artistic pursuits in general. You're too busy focusing on the practical: fixing the chain saw, getting your wood inside when it's 60 below, hauling water in buckets. It's easier to write short essays that get published right away."

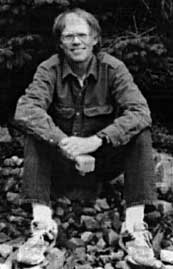

Proof of the lean toward nonfiction can be found in a recently modified Alaska State Council on the Arts program. Recently, the council announced that Richard K. Nelson (photo at right) was selected as the new "Alaska State Writer," a two-year honorary position that replaces the less broadly defined poet laureate. "We wanted to bring attention to the wealth we have in terms of literary artists," said associate director Shannon Planchon. Among Nelson's powerful and major works of nonfiction are Make Prayers to the Raven, The Island Within, and Hunters of the Northern Forest. In two years, the next State Writer will be a poet. Playwrights may be honored in the future.

Proof of the lean toward nonfiction can be found in a recently modified Alaska State Council on the Arts program. Recently, the council announced that Richard K. Nelson (photo at right) was selected as the new "Alaska State Writer," a two-year honorary position that replaces the less broadly defined poet laureate. "We wanted to bring attention to the wealth we have in terms of literary artists," said associate director Shannon Planchon. Among Nelson's powerful and major works of nonfiction are Make Prayers to the Raven, The Island Within, and Hunters of the Northern Forest. In two years, the next State Writer will be a poet. Playwrights may be honored in the future.

Of course, Alaska regularly attracts Outside writers ready to try their hand at demystifying the state. Jon Krakauer's Into the Wild sold far better than most homegrown books. Several Alaska writers expressed chagrin at Krakauer's success. As Nancy Lord said, 'There's certainly a place for the Outside writer being a fresh set of eyes. But I think the strongest writing is coming from people who live here now."

Mistresses (and Masters) of Mystery

Literary fiction may be rare in Alaska, but mass-market fiction rolls into bookstores as regularly as a bore tide. Audiences have a handful of prolific authors to thank. Starting in the early 1990s, mystery authors Sue Henry and Dana Stabenow made blood and snow seem the most obvious of pairings.

Stabenow, perennially selected by Anchorage readers as a favorite author, has published 14 books in a decade, among them Hunter's Moon, Breakup and Fire and Ice. A new book, Midnight Come Again, will appear in May.

Henry, author of Dead Fall, Death Takes Passage and Murder on the Yukon Quest, is working on book No. 8. Her first mystery, Murder on the Iditarod Trail, will be reissued this winter with a new cover. Beneath the Ashes, a Mat-Su arson mystery, will appear next summer.

Neither woman keeps track of how many books she has sold (somewhere in the hundreds of thousands, each estimates). Apparently fearless of competition, they are gregarious boosters of the mystery genre. A comparative newcomer, Megan Mallory Rust (Red Line and Dead Stick), was a student in one of Henry's creative writing classes.

"She was one of two who I thought had real potential," Henry said. "I'm still waiting for the other one."

Can there really be more room? Anchorage author Stan Jones joined an already crowded field when he published his first mystery, White Sky, Black Ice, last May.

Shamus Award-winner John Straley, who flavors his mysteries with raven-black humor, published his first, The Woman Who Married a Bear, in 1992. He's published four others since then. His most recent, The Angels Will Not Care, will appear in paperback in February.

Having spawned so many mystery writers in the last decade, Alaska will soon host its first mystery convention, Left Coast Crime, in February 2001. The conference will draw the genre's top writers, some of whom may travel farther to visit schoolchildren around the state, Stabenow said.

"I would have killed for a writer to walk into my classroom when I was a kid growing up in the Bush," said Stabenow, who was raised in Cordova and Seldovia. "I'd be 20 years ahead of where I am now as a writer."

Beyond Alaska

Alaskana may be marketable, but some writers and editors whose work extends beyond the state's borders still find literary and commercial success. That's one indication our literary community is maturing said essayist Jans, who selected Shackleton: The Antarctic Challenge by Kim Heacox as a notable book of the 1990s. "Finally, Alaska writers don't have to write only about Alaska," he said.

Along the same lines, Alaska publications need not limit themselves to in-state writers. That's been Alaska Quarterly Review editor Spatz's view all along. The award-winning UAA literary journal draws contributions from around the world -- Chile, Japan, France -- while still making room for the best works of local writers. A 1997 special issue, Intimate Voices, Ordinary Lives: Stories of Fact and Fiction, included pieces by Wendy Erd, Nancy Lord, Gary Holthaus and Leslie Leyland Fields.

'Of 27 pieces, four are distinctly Alaskan,' Spatz said. 'How much do you need? When you're putting spices together in a world-class curry, you're not going to dump in three pounds of pepper.'

AQR's refusal to play a purely provincial role is one reason local readers don't necessarily know about the book-sized journal. But anthologists do. AQR's latest kudo comes in the form of a new anthology called The Beacon Best of 1999: Creative Writing by Women and Men of All Colors. Five pieces that originally appeared in AQR were selected. By comparison, only four pieces were selected from The New Yorker; from Esquire, only one.

'That one of the nation's best literary magazines comes out of Alaska may seem surprising, but so it is," announced The Washington Post two years ago.

That quote, to be savored into the next decade, suggests that Alaska isn't such a remote literary outpost after all.

The Future

Whether writing for New York or Anchorage, about Alaska or Antarctica, many authors describe Alaska as a friendly place for writers to learn and live their craft. That may help Alaska literature develop in decades to come.

University of Alaska campuses in both Anchorage and Fairbanks have strong writing programs. The Alaska Center for the Book has sponsored symposiums and literacy programs since 1991.

In Anchorage, the Writing Rendezvous has brought authors, publishers and readers together since 1994. In Sitka, the Island Institute hosts an annual summer symposium that is more about ideas and values than about writing, but which brings national-caliber writers together all the same.

'The writing circles here are small enough that you'll run into the same people over and over again, and that helps elevate all of us," said Sherry Simpson.

The cooperative nature of book writing and publishing here is a great advantage, Jans said.

'There's no reason we couldn't develop a regional literature that's more than just regional, like the literary group in Paris, post-World War I, or in the (U.S.) South in the 1930s and 1940s. We are loosely allied writers, all telling the same stories from different perspectives."

"I don't feel competition here," Jans added. "I feel camaraderie. Anyone who is trying to get the story right is my partner and my friend."

This article originally appeared in We Alaskans, the Sunday magazine section of The Anchorage Daily News, and is reprinted with permission. This version is slightly different than the one that appeared in The Anchorage Daily News.

The photos of Nancy Lord and Richard Nelson are by Linda Smoger and Nita Counchman respectively.