|

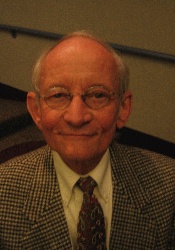

Ted Kooser presented this speech at the American College of Physicians-Alaska Chapter meeting (http://www.acponline.org/meetings/chapter/ak-2008.pdf) on June 26, 2008.

|

| Ted Kooser |

|

You're going to have to sit there and look at me for awhile, and I thought that as long as you're looking at me, I'd tell you a little anecdote that will enhance the looking. Shortly after I was named Poet Laureate of the United States, there was a lot of press coverage. The Los Angeles Times ran a banner story, I think on one of their section fronts inside, about the new Poet Laureate, and it had a little mug shot of me in there, so everybody reading the LA Times was looking at this. I have a friend who for many years has been an aspiring screenwriter in Hollywood, and he had a copy of the Times, and he was showing it to the neighbor boy, whose name was Buck, and Buck was at this time I guess about eight years old. So Tom read the story to Buck, and then he began elaborating on, "Well, a Poet Laureate might do this, and a Poet Laureate might do that," and so on. So after awhile he said to Buck, "So what do you think about this?" And Buck said, "I think he looks like a hobbit. Like he came from Middle Earth."

I am at base an introvert, and it's never been easy for me to get up in front of groups of people. When this happened to me, I knew that I was going to be in front of groups of people, and so on. My friends, knowing that I was an introvert, would come up to me and put a hand on my shoulder and say, "How are you doing with this? How are you getting along? How's Kathy like it? Is she getting along okay with it? How about the dogs? How do they feel about this?" and that sort of thing. So I wrote this poem to respond to those. Here's a little poem about my elevation to celebrity:

Success

I can feel the thick yellow fat of applause

building up in my arteries, friends,

yet I go on, a fool for adoration. Do I care

that when it sloughs off, it is likely to go

straight to the brain? I'm already showing

the first signs of poetic aphasia,

the words coming hard, the synapses

of metaphor no longer connecting.

But look at me, down on my knees

next to the podium, lapping the last drops,

then rolling in the stain like a dog,

getting the smell in my good tweed sport coat,

the grease on my suede elbow patches,

and for what? Well, for the women I walk past

the next morning, the ones in the terminal,

wheeling their luggage, looking so beautifully

earnest. All for the hope that they will

suddenly dilate their nostrils, squeeze

the hard carry-on handles, and rise to

the ripening odor of praise with which I have

basted myself, stinking to heaven.

I wanted to read one poem about the area where I live. I live in eastern Nebraska, about 20 miles from Lincoln. We live on an acreage of 60 acres, roughly. I really love my state, and this is a poem I wrote, I suppose 25 years ago. What had happened was that William Kloefkorn, who is the Nebraska state poet, I ran into him one morning and he said, "Are you going to that literary thing out at Grand Island?" I said, "I don't think I know about that." He said, "Oh, they invited all of us to come out and read poems and so on." I said, "Well, Bill, they didn't invite me." So I thought about it a minute, and I said, "I'll tell you what I'm going to do. I'm going to go home and write a poem, and I want you to take it out there and read it on my behalf at this thing."

So I went home with the idea that I was going to write a real snotty poem about Nebraska writers and their myopia and so on, and I started this poem -- ordinarily I work on a poem for days, you know, in revision and so on, but this one I needed to get done by the next morning, so I was up pretty much all night working on it. And what was interesting about it was that as the poem developed, I began to realize how much I really loved my state, so the whole tone of the poem changed throughout.

So This Is Nebraska

The gravel road rides with a slow gallop

over the fields, the telephone lines

streaming behind, its billow of dust

full of the sparks of redwing blackbirds.

On either side those dear old ladies,

the loosening barns, their little windows

dulled by cataracts of hay and cobwebs,

hide broken tractors under their skirts.

So this is Nebraska. A Sunday

afternoon; July. Driving along

with your hand out squeezing the air,

a meadowlark waiting on every post.

Behind a shelterbelt of cedars,

top-deep in hollyhocks, pollen, and bees,

a pickup kicks its fenders off

and settles back to read the clouds.

You feel like that. You feel like letting

your tires go flat, like letting the mice

build a nest in your muffler, like being

no more than a truck in the weeds,

clucking with chickens or sticky with honey

or holding a skinny old man in your lap

while he watches the road, waiting

for someone to wave to. You feel like

waving. You feel like stopping the car

and dancing around on the road. You wave

instead and leave your hand out gliding

larklike over the wheat, over the houses.

Not all the Great Plains are filled with bucolic beauties and so on. I was out in the middle of Nebraska. Nebraska, you know, is a good-sized state. It's 10 hours to drive across. One of my recreations is to go out and drive around small towns, and I'll talk about that more. One day I was out near Ord, Nebraska, right in the center of the state, sparsely populated, and by the side of the road there was a fenced-in square, probably about the same size as this area, but nothing in it that I could see, but it had been fenced and had a gate on it. So I drove down the road, and there was a man working in a field there, and I talked to him. I said, "What's that back there?" He said, "Well, that's where the County Poor Farm used to be." And then he told me about that, and this is a poem about that place.

Site

A fenced-in square of sand and yellow grass,

five miles or more from the nearest town

is the site where the County Poor Farm stood

for seventy years, and here the County

permitted the poor to garden, permitted them

use of the County water from a hand-pump,

lent them buckets to carry it spilling

over the grass to the sandy, burning furrows

that drank it away -- a kind of Workfare

from 1900. At night, each family slept

on the floor of one room in a boxy house

that the county put up and permitted them

use of. It stood here somewhere, door

facing the road. And somewhere under this grass

lie the dead in the County's unmarked graves,

each body buried with a mason jar in which

each person's name is written on a paper.

The County provided the paper and the jars.

I was reading some poems this morning that were quite personal about cancer recovery, and I wanted to do something different tonight. My favorite point of view as a poet is to stay out of the poems, notice something happening, and capture it as best I can, so there are very few "I's" in any of my poems. Here's a little group of short poems that are very much like snapshots.

Tattoo

What once was meant to be a statement --

a dripping dagger held in the fist

of a shuddering heart -- is now just a bruise

on a bony old shoulder, the spot

where vanity once punched him hard

and the ache lingered on. He looks like

someone you had to reckon with,

strong as a stallion, fast and ornery,

but on this chilly morning, as he walks

between the tables at a yard sale

with the sleeves of his tight black T-shirt

rolled up to show us who he was,

he is only another old man, picking up

broken tools and putting them back,

his heart gone soft and blue with stories.

What I like to do in my poems (and you'll probably pick up on this on your own), I like to set up a sort of central metaphor, a comparison or an association between two things and then stretch it a little bit until I get to the point that I can fill the whole poem with that one kind of figure. And this one is about the motion that a woman was making pushing a wheelchair, that motion.

A Rainy Morning

A young woman in a wheelchair,

wearing a black nylon poncho spattered with rain,

is pushing herself through the morning.

You have seen how pianists

sometimes bend forward to strike the keys,

then lift their hands, draw back to rest,

then lean again to strike just as the chord fades.

Such is the way this woman

strikes at the wheels, then lifts her long white fingers,

letting them float, then bends again to strike

just as the chair slows, as if into a silence.

So expertly she plays the chords

of this difficult music she has mastered,

her wet face beautiful in its concentration,

while the wind turns the pages of rain.

For a number of years, 22 years to be exact, I wrote an annual valentine poem. I began by sending them to the wives of my friends, and then that list began to grow, and then when I sort of went on the road as Poet Laureate I began to ask audiences, I'd say, "If there are any women in this audience who'd like to be on my valentine list, give me your name and address." So by Valentine's Day last year, I had 2,700 names on my list. I write the poem and have it printed on a little postcard. But last year, that year, the postage and the printing were about $1,000, and I thought, "You know, you've probably carried this far enough," so I gave it up. But I wanted to read one of these valentines. This is one of my favorite ones. This is the one from 2004. Again, here I am looking at something happening.

Splitting an Order

I like to watch an old man cutting a sandwich in half,

maybe an ordinary cold roast beef on whole wheat bread,

no pickles or onion, keeping his shaky hands steady

by placing his forearms firm on the edge of the table

and using both hands, the left to hold the sandwich in place,

and the right to cut it surely, corner to corner,

observing his progress through glasses that moments before

he wiped with his napkin, and then to see him lift half

onto the extra plate that he asked the server to bring,

and then to wait, offering the plate to his wife

while she slowly unrolls her napkin and places her spoon,

her knife and her fork in their proper places,

then smooths the starched white napkin over her knees

and meets his eyes and holds out both old hands to him.

I also have been trying to come up with a way of writing poems in which there are two figures, like those in that poem, and I've done several. Here's another one. This is really quite a recent poem, just several months old now.

Two Men on an Errand

The younger, a balloon of a man

in his sixties with some of the life

let out of him, sags on the cheap couch

in the car repair shop's waiting room.

Scuffed shoes, white socks, blue trousers,

a nondescript gray winter jacket.

His face is pale, and his balding head

nods with some kind of palsy. His fists

stand like stones on the tops of his thighs --

white boulders, alabaster -- and the flesh

sinks under the weight of everything

he's squeezed within them. The other man

is maybe eighty-five, thin and bent

over his center. One foot swollen

into a foam rubber sandal, the other

tight in a hard black shoe. Blue jeans,

black jacket with a semi tractor

appliqued on the back, white hair

fine as a cirrus cloud. He leans

forward onto a cane, with both hands

at rest on its handle as if it were

a steering wheel. The two sit hip to hip,

a bony hip against a fleshy one,

talking of car repairs, about the engine

not hitting on all the cylinders.

It seems the big man drove them here,

bringing the old man's car, and now

they are waiting, now they have to wait

or want to wait until the next thing

happens, and they can go at it

together, the younger man nodding,

the older steering with his cane.

Another little snapshot:

Skater

She was all in black but for a yellow ponytail

that trailed from her cap, and bright blue gloves

that she held out wide, the feathery fingers spread,

as surely she stepped, click-clack, onto the frozen

top of the world. And there, with a clatter of blades,

she began to braid a loose path that broadened

into a meadow of curls. Across the ice she swooped

and then turned back and, halfway, bent her legs

and leapt into the air, the way a crane leaps, blue gloves

lifting her lightly, and turned a snappy half-turn

there in the wind before coming down, arms wide,

skating backward right out of that moment, smiling back

at the woman she'd been just an instant before.

The more ordinary the subject matter, the more it appeals to me, and the more I want to capture it. I would like to convince readers of my poetry that the ordinary world is full of beautiful things. This is a picture of my wife, Kathleen, washing her hands at the kitchen sink.

A Washing of Hands

You turned on the tap and a silver braid

unraveled over your fingers.

You cupped them, weighing that tassel,

first in one hand and then the other,

then pinched through the threads

as if searching for something, perhaps

an entangled cocklebur of water

or the seed of a lake. A time or two

you took the tassel in both hands,

squeezed it into a knot, wrung out

the cold and the light, and then, at the end,

pulled down hard on it twice,

as if the water were a rope and you were

ringing a bell to call me, two bright rings,

though I was there.

I work with graduate students in creative writing at the University of Nebraska. I have a half-time appointment. I teach only in the fall. But I work one-on-one with my students tutorially, and I really like doing it that way. I usually have 12 or 13, and I see them each an hour a week. This poem was written quite awhile back now, but it was written to, in a way, illustrate to students that when they write about their feelings, they should come at the feelings from a slant, the way Emily Dickinson would have talked about it, that declarations of feeling, flat declarations of feeling don't work. You have to figure out a way of conveying great feeling in another way.

What had happened -- I was in downtown Lincoln, Nebraska, one day, and across the street I saw a woman with whom I had been in love about 20 years before, and she didn't see me. I just saw her pass by, but it was really a tremendously moving thing for me. It really kicked the air out of me to see her after all those years. So this poem attempts to get at those feelings without overtly declaring them.

After Years

Today, from a distance, I saw you

walking away, and without a sound

the glittering face of a glacier

slid into the sea. An ancient oak

fell in the Cumberlands, holding only

a handful of leaves, and an old woman

scattering corn to her chickens looked up

for an instant. At the other side

of the galaxy, a star thirty-five times

the size of our own sun exploded

and vanished, leaving a small green spot

on the astronomer's retina

as he stood in the great open dome

of my heart with no one to tell.

I write lots of poems about things, too, ordinary things around the house.

The Leaky Faucet

All through the night, the leaky faucet

searches the stillness of the house

with its radar blip: who is awake?

Who lies out there as full of worry

as a pan in the sink? Cheer up,

cheer up, the little faucet calls,

someone will help you through your life.

Home Medical Dictionary

This is not so much a dictionary

as it is an atlas for the old,

in which they pore over

the pink and gray maps of the body,

hoping to find that wayside junction

where a pain-rutted road

intersects with the highway

of answers, and where the slow river

of fear that achingly meanders

from organ to organ

is finally channeled and dammed.

A spiral notebook. There's nothing more common than spiral notebooks. Every drugstore in the country has three or four hundred of them on the shelves. That's the kind of thing I like to work with.

A Spiral Notebook

The bright wire rolls like a porpoise

in and out of the calm blue sea

of the cover, or perhaps like a sleeper

twisting in and out of his dreams,

for it could hold a record of dreams

if you wanted to buy it for that,

though it seems to be meant for

more serious work, with its

college-ruled lines and its cover

that states in emphatic white letters,

5 SUBJECT NOTEBOOK. It seems

a part of growing old is no longer

to have five subjects, each

demanding an equal share of attention,

set apart by brown cardboard dividers,

but instead to stand in a drugstore

and hang onto one subject

a little too long, like this notebook

you weigh in your hands, passing

your fingers over its surfaces

as if it were some kind of wonder.

I love to read this poem. I read it at every reading. Because what happens, what we do with poems like, let's say the wheelchair poem, is that I catch you in this comparison I'm working on, for this woman in her wheelchair looking like she's striking keys of a piano, and as the poem progresses, I squeeze you a little bit. And then in the end, if the poem works, I let you loose and you feel this sort of "Ha!" at the end of the poem, because I've compressed it down to that. But this one is a lot of fun to read because I will be able to observe you growing more and more uncomfortable as the poem goes. I want you to know that I'll let you out at the end of it. This is particularly appropriate for this audience. This was in the Journal of the American Medical Association, gosh, 25 years ago probably.

The Urine Specimen

In the clinic, a sun-bleached shell of stone

on the shore of the city, you enter

the last small chamber, a little closet

chastened with pearl -- cool, white, and glistening,

and over the chilly well of the toilet

you trickle your precious sum in a cup.

It's as simple as that. But the heat

of this gold your body's melted and poured out

into a form begins to enthrall you,

warming your hand with your flesh's fevers

in a terrible way. It's like holding

an organ -- spleen or fatty pancreas,

a lobe from your foamy brain still steaming

with worry. You know that just outside

a nurse is waiting to cool it into a gel

and slice it onto a microscope slide

for the doctor, who in it will read your future,

wringing his hands. You lift the chalice and toast

the long life of your friend there in the mirror,

who wanly smiles but does not drink to you.

One of my best friends in Nebraska is a noted landscape painter by the name of Keith Jacobshagen. He grew up in Kansas. He does beautiful oil landscapes, very wide, low horizon, these beautiful open plains skies. He has been very successful with these. When I'm around home, his wife and my wife and Keith and I sometimes go to dinner. One night he told me a family story at dinner, and it was all I could do to keep from making notes right on the tablecloth, I loved it so much. So this is Keith's story, really, that I've rewritten. The old man who appears in this poem is Keith's maternal great-grandfather, and the young woman whose body is coming back to Kansas on the train would have been Keith's maternal grandmother's older sister. Those of you who may have read Willa Cather at some time in your schooling, in a way this is sort of like a Willa Cather story.

The Beaded Purse

Dressed in his church suit and under

the shadow of his hat, the old man

stood on the wooden depot platform

three feet above the rest of Kansas

while the westbound freight chuffed in

and hissed to a stop. He and the agent

and two men, commercial travelers

waiting to go on west, pulled mailbags

out of the steam, then slid out

his daughter's coffin, canvas over wood,

and set it on a nearby baggage cart.

Not till the train had rolled away

and tooted once as it passed the shacks

on the leading edge of the distance,

and not till the agent had disappeared,

dragging the bags of mail behind,

did the old man pry up the nailed-down lid

with a bar he'd brought in the wagon.

Hat in hand, he took a long look.

He hadn't seen her in a dozen years.

At nineteen, without his blessing,

she'd gone back east to be an actress,

now and then writing her mother

in a carefree, ne'er-do-well cursive

to say she was happy, living in style.

A week before, the agent sent word

that there was a telegram waiting,

and the old man and his wife rode to town

to read that their daughter had died

and her remains were on the way home.

Remains, that's how they put it.

She was wearing a fancy yellow dress

but was no longer young and pretty.

She looked like one of the worn-out dolls

she'd left in her room at the farm

where he would sometimes go to sit.

A bag of women's private underthings

had been stuffed between her feet,

and someone had pushed down next to her

an evening bag, beaded with pearls.

He opened the purse and found it empty,

so he took a few bills out of his pocket

and folded them in, then snapped it closed

for her mother to find. Then, with the back

of the bar he tapped the lid in place

and went to find the station agent.

The two of them lifted the coffin down

and carried it a few hard yards across

the sunny, dusty floor of Kansas

and loaded it onto the creaking wagon.

Then, clapping his hat on his head

and slapping the plump rump of the mare

with the reins, he started the long haul home

with his rich and famous daughter.

How's that for a gesture? Isn't that amazing?

I was very fond of my family, and I've written a lot of poems about particularly my mother's side. I happened one day on a photograph of a couple who were my great-uncle and great-aunt, who lived way into their 90s and were married for 70 years. In this photograph -- it's a studio photograph taken in a little studio in Guttenberg, Iowa -- the two of them are sitting side by side on kind of a bench, and there's a good deal of space between them, sort of heavy space between them.

An Old Photograph

This old couple, Nils and Lydia,

were married for seventy years.

Here they are sixty years old

and already like brother

and sister -- small, lustreless eyes,

large ears, the same serious line

to the mouths. After those years

spent together, sharing

the weather of sex, the sour milk

of lost children, barns burning,

grasshoppers, fevers and silence,

they were beginning to share

their hard looks. How far apart

they sit, not touching at shoulder

or knee, hands clasped in their laps

as if under each pair was a key

to a trunk hidden somewhere,

full of those lessons one keeps

to himself.

They had probably

risen at daybreak, and dressed

by the stove, Lydia wearing

black wool with a collar of lace,

Nils his worn suit. They had driven

to town in the wagon and climbed

to the studio only to make

this stern statement, now veined

like a leaf, that though they looked

just alike, they were separate people,

with separate wishes already

gone stale, a good two feet of space

between them, thirty years to go.

I talked a little in my session earlier today about the value of writing about family and how you don't have to write well about family, all you have to do is write as much down as you can remember and put it away somewhere, and then someday, perhaps years after you're gone, someone will pick up that thing and read it, and all of a sudden some person who's been dead for 30 or 40 years comes back up into the light for a little while and then subsides. And I wrote this poem very intentionally that way. My mother had a first cousin, again up in northeastern Iowa, and I was very fond of him from the time I was a little boy. He was a very jolly German and Swiss combination, and what had happened was that I had heard in Nebraska from my mother, who told me that he was quite ill and that he wasn't expected to live too long, and he was in a nursing home in Guttenberg, which is quite a long ways from where I live, but I happened to be in Cedar Rapids, so I drove up to Guttenberg to see him in the nursing home. They knew I was coming, and they'd gotten him all dressed in a brand-new plaid shirt, sitting in a wheelchair out in the visitors' area in the nursing home. Like a lot of older people (and you see many of these people), he had developed a very pronounced, very dark age spot on one hand that went up into the sleeve of his shirt, and that figures in this poem.

A Good-bye Handshake

Though you and the nursing home

are miles behind me now, your hand

with its dark blue age spots

is here in my hand, your fingers warm

from all of the hot steel handles

they held in your eighty-eight years --

levers of threshing machines,

of sickle-bar mowers and balers --

but cooling now and slowly going

all blue-black over brown, like a pool

of blue oil on the floor of a barn,

that darkness working its way up

into the cuff of your new plaid shirt,

up past your elbow, sharp as a plowshare

there on the wheelchair armrest,

easing over your heart like a shadow.

A hundred miles down the road, stopped by

the highway and sitting in shade

at the edge of a shimmering cornfield,

I say good-bye. I am headed both farther

and further than you, Ira Friedlein.

With love I take your blue-black hand,

which has held nearly everything once,

and squeezed it shyly and politely.

And here's my dear grandmother throwing the dishwater off the back step.

Dishwater

Slap of the screen door, flat knock

of my grandmother's boxy black shoes

on the wooden stoop, the hush and sweep

of her knob-kneed, cotton-aproned stride

out to the edge and then, toed in

with a furious twist and heave,

a bridge that leaps from her hot red hands

and hangs there shining for fifty years,

over the mystified chickens,

over the swaying nettles, the ragweed,

the clay slope down to the creek,

over the redwing blackbirds and the tops

of the willows, a glorious rainbow

with an empty dishpan hanging at one end.

Aunt Mildred. You've probably all known women like this one. My mother was very much like this, was a penny-pincher really, and that generation of women really thrived on it. They loved doing without, I think.

Aunt Mildred

After she'd cooked and then eaten the meat,

she washed and rinsed the butcher paper

under a pitcher pump that drew red water

up from a cistern under the house, rain

speckled with dirt from the cedar shingles,

then put the paper out on the line to dry,

using old clothespins whitened by lye

(the paper pinned next to her underthings,

which she dried inside her pillowcases

so they couldn't be seen from the street),

then pressed the paper with a hot sadiron

and carefully cut it into little squares,

picked up a pencil stub and pinched it hard,

straightened her spine, and wrote a small

but generous letter to the world.

My mother lived to be 89, and was able to stay in her house until the last few months. My dad had been gone for 20 years by that time. One of the things she was doing was she'd go out to garage sales and she'd buy a bag of fabric scraps, and then she'd piece together these crazy quilt tops, beautiful things, feather-stitched, with all that stuff. They were never quilted, they were tied comforters really, but they had all the flair of the crazy quilting. Our family, my generation and the one that follows, are really quite small, and she had given one of these to all of the members of the family. And I called her up one day to see how she was doing. She would never call me, because she wouldn't spend the money to do that. I called her, and she said, "Ted, I just finished another one of these quilts. I have no one to whom to give it. What do you think?" I said, "Well, what do you have in that quilt, mother?" She said, "Twelve dollars and 43 cents." This is a woman, by the way, that when she died, I took home from her house the spiral notebooks that she had kept. She and my father were married in 1937, and from 1937 until she died in 1998, she wrote down every cent that she spent in those notebooks.

Anyway, she said 12 dollars and 43 cents, and I said, "Well, what if I were to give you 75 or a hundred dollars for that?" She said, "Well, why would you do that?" I said, "Well, a former girlfriend of mine from between my marriages got married about a year ago and I didn't give her a wedding present, and I thought something like this would make a really nice wedding present," and without pausing for a breath, she said, "Ted, that's too much to give to an old girlfriend." And she wouldn't let me have it. I never got it. Afraid that I would give it away anyway, you know. Well, here's a poem about Mother. She died on the 23rd of March, 1998, and about a month later -- my birthday's April 25 -- I decided I would write her a letter to tell her what she'd missed in that month.

Mother

Mid April already, and the wild plums

bloom at the roadside, a lacy white

against the exuberant, jubilant green

of new grass and the dusty, fading black

of burnt-out ditches. No leaves, not yet,

only the delicate, star-petalled

blossoms, sweet with their timeless perfume.

You have been gone a month today

and have missed three rains and one nightlong

watch for tornadoes. I sat in the cellar

from six to eight while fat spring clouds

went somersaulting, rumbling east. Then it poured,

a storm that walked on legs of lightning,

dragging its shaggy belly over the fields.

The meadowlarks are back, and the finches

are turning from green to gold. Those same

two geese have come to the pond again this year,

honking in over the trees and splashing down.

They never nest, but stay a week or two,

then leave. The peonies are up, the red sprouts

burning in circles like birthday candles,

for this is the month of my birth, as you know,

the best month to be born in, thanks to you,

everything ready to burst with living.

There will be no more new flannel nightshirts

sewn on your old black Singer, no birthday card

addressed in a shaky but businesslike hand.

You asked me if I would be sad when it happened

and I'm sad. But the iris I moved from your house

now hold in the dusty dry fists of their roots

green knives and forks as if waiting for dinner,

as if spring were a feast. I thank you for that.

Were it not for the way you taught me to look

at the world, to see the life at play in everything,

I would have to be lonely forever.

On the morning after Mother's death, I was in Cedar Rapids at her bedside when she died, and I decided -- I couldn't sleep much during that night, and I decided about four in the morning I would drive up to Guttenberg, where her best friend was still in a nursing home there, and let her know that this had happened. I got there about breakfast time in the nursing home, and this woman who we always called Aunt Sticky -- her maiden name was Stickford, and we called her Aunt Sticky -- she was having her breakfast in her room. She knew what I'd come for. She said that Mother had written and said she wasn't very good and not doing well, and so on, so she wasn't surprised. Then she paused and said this beautiful thing. She said, "Your mother and I were such good friends, Ted, that we could sit in a room together for an hour and neither of us thought we had to say a word."

Well, I left her and I decided I would tell Mother's last remaining first cousin, Pearl Richards, who was a year older than Mother, the news. Pearl lived in Elkader, which is another town back from the Mississippi River on the Turkey River, about another 20 miles. This is an account of my meeting with Pearl that day at her little house.

Pearl

Elkader, Iowa, a morning in March,

the Turkey River running brown and wrinkly

from a late spring snow in Minnesota,

the white two-story house on Mulberry Street,

windows flashing with sun, and I had come

a hundred miles to tell our cousin, Pearl,

that her childhood playmate, Vera, my mother,

had died. I knocked and knocked at the door

with its lace-covered oval of glass, and at last

she came from the shadows and with one finger

hooked the curtain aside, peered into my face

through her spectacles, and held that pose,

a grainy family photograph that could have been

that of her mother. I called out, "Pearl,

it's Ted. It's Vera's boy," and my voice broke,

for it came to me, nearly sixty, I was still

my mother's boy, that boy for the rest of my life.

Pearl, at ninety, was one year older than Mother

and a widow for twenty years. She wore

a pale blue cardigan buttoned over a housedress

and she shook my hand in the tentative way

of old women who rarely have hands to shake.

When I told her that Mother was gone, that she'd

died the evening before, she said she was sorry,

that "Vera wrote me a letter awhile ago

to say she wasn't good." We went to the kitchen

and I sat at the table while she heated a pan

of water and made us cups of instant coffee.

She told me of a time when the two of them

were girls and crawled out onto the porch roof

to spy on my Aunt Mabel and a suitor

who were swinging below. "We got so excited

we had to pee and we couldn't wait, and peed

right there on the roof and it trickled down

over the edge and dripped in the bushes

but Mabel and that fellow never heard!"

We took our cups into her living room

where stripes from the drawn blinds draped over

the World's Fair satin pillows. She took the couch

and I took a chair across from her. "I've had

some trouble with health myself," she said,

taking off her glasses and wiping them,

and I said she looked good, though, and she said,

"I've started seeing people who aren't here.

I know they're not real but I see them the same.

They come in the house and sit around

and never say a word. They keep their heads down

or cover their faces with cloths. I'm not afraid,

but I don't know what they want of me.

You won't be able to see, but one's right there

on the staircase where the light falls through

that window, a man in a light gray outfit."

I turned to look at the landing, where a patch

of light fell over the carpeted steps.

"Sometimes I think that my Max is with them;

one seems to know his way around the house.

What bothers me, Ted, is that they've started

to write out lists of everything I own.

They go from room to room, three or four

at a time, picking up things and putting them back.

I talked to Wilson, the chiropractor,

and he just says that maybe it's time for me

to go to the nursing home." I asked her

what her regular doctor said and she said

she didn't go there anymore, that "He's

not much good." "But surely there's medicine,"

I said, and she said, "Maybe so." And then

there was a pause that filled the room.

After a while we began to talk again,

of other things, and there were some stories

we laughed a little over, and I wept a little,

and then it was time for me to go, to drive

the long miles back, and she slowly walked me

to the door and took my hand again --

our warm bony hands among the light hands

of the shadows that reached to touch us but

drew back -- and I cleared my throat and said

I hoped she'd take care of herself, and think

about seeing a real medical doctor,

and she said she'd give some thought to that,

and I took my hand from hers and waved goodbye

and the door closed, and behind the lace

the others stepped out of the stripes of light

and resumed their inventory, touching

the spoon I used and subtracting it from

the sum of the spoons in the kitchen drawer.

I'm going to read one more poem about the family, and then I'm going to close with one. Here's a medical subject for this one. This is about my father, who had sleep apnea before anyone as far as we knew had ever come up with a diagnosis of that. There were four of us in the family, and I can't imagine the number of nights that my mother, my sister, and I lay there staring wide-eyed at the ceiling when Dad's breathing would stop altogether and then pick up again.

Sleep Apnea

Night after night, when I was a child,

I woke to the guttering candle

of my father's breath. It made a sound

like the starlings that sometimes

got caught in our chimney, a chirping

that would gradually, steadily build

to a desperate, flat slapping of wings,

then suddenly drop into silence,

into the thick soot at the bottom

of midnight. No silence was ever

so deep. And then, after maybe

a minute or two, I would hear

a twitter as he came to life again,

and could at last take a breath for myself,

a sip like a toast, lifting a chilled glass

of air, wishing us courage, those of us

lying awake through those hours,

my mother, my sister, and I, who each night

listened to death kiss the fluttering lips

of my father, who slept through it all.

This will be my last one. I mentioned that I like to drive around in the country and so on. One day I'd gotten back from a tour of some little towns close to where I live, and I got to thinking, "I wonder how I look to these people?" You know, there's this stranger there, walking up and down the street, peering in windows and so on.

That Was I

I was that older man you saw sitting

in a confetti of yellow light and falling leaves

on a bench at the empty horseshoe courts

in Thayer, Nebraska -- brown jacket, soft cap,

wiping my glasses. I had noticed, of course,

that the rows of sunken horseshoe pits

were like old graves, but I was not letting

my mind go there. Instead I was looking

with hope to a grapevine draped over

a fence in a neighboring yard, and knowing

that I could hold on. Yes, that was I.

And that was I, the round-shouldered man

you saw that afternoon in Rising City

as you drove past the abandoned Mini Golf,

fists deep in my pockets, nose dripping,

my cap pulled down against the wind

as I walked the miniature Main Street

peering into the child-sized plywood store,

the poor red school, the faded barn, thinking

that not even in such an abbreviated world

with no more than its little events -- the snap

of a grasshopper's wing against a paper cup --

could a person control this life. Yes, that was I.

And that was I you spotted that evening

just before dark, in a weedy cemetery

west of Staplehurst, down on one knee

as if trying to make out the name on a stone,

some lonely old man, you thought, come there

to pity himself in the reliable sadness

of grass among graves, but that was not so.

Instead I had found in its perfect web

a handsome black and yellow spider

pumping its legs to try to shake my footing

as if I were a gift, an enormous moth

that it could snare and eat. Yes, that was I.

Thank you very much.

|

|

|