|

Tom Richards: Thank you, Sam. I met our next speaker in about 1967 or 1968. He was active on the services side with Alaska Legal Services and then with RurALCAP.

John Shively: No, no, no. I’m not a lawyer. I wouldn’t have spent all that money on them.

Tom Richards: John Shively. I misspoke.

|

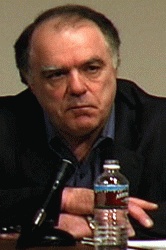

| John Shively |

|

John Shively: It’s okay, Tom, you’re still my buddy. I’ve been called worse, but not much.

Tom Richards: After RurALCAP and after the enactment of the Native Claims Settlement Act, John Shively was one of the first employees and key officers with the NANA Regional Corporation. He served with NANA from the beginning of ANCSA. He took a brief break to serve as chief of staff for Governor Sheffield during the Sheffield administration, and then returned to NANA and later retired as NANA’s senior vice president. John, we’re going to ask you to talk about some of the key amendments, including the NOLs, net operating losses, which may have saved a few corporations from dissolution.

John Shively: I thought Sam was going to talk about NOLs? Let me just say a few things. I did come to Alaska in 1965 as a VISTA volunteer and fully intended to return home a year later, which was the end of my tour. But I got assigned to Yakutat, my second assignment, and there was a young man down there named Byron Mallott. It was really Byron who got me interested in the Native land issues. I had to be in Anchorage the week before the Alaska Natives came together for the first time on a statewide basis in October of 1966, the meeting out of which AFN was formed. Byron said, “You might want to stay around, I think this would be interesting. It might be interesting to you.” Well it was, at least the parts that they let me attend since I was not Native. In those days they often closed parts or all of their sessions to non-Natives.

What struck me at the 1966 meeting was a speech by a gentleman named Nick Gray, who I think most people have forgotten. Nick was from the Bering Straits area and he had been responsible for setting up organizations like the Cook Inlet Native Association. I think he was also instrumental in setting up the Fairbanks Native Association and one of the Bethel organizations. He had a vision fore Natives to come together to work on issues.

Nick had been in the hospital with leukemia and he came out of the hospital to give what was, to me, one of the most stirring speeches about why Natives needed to work together to solve their problems. It was a defining moment for me personally, and I think for others in the room. Nick passed away within weeks of that meeting, but the spirit that Nick saw of bringing people with diverse cultures together to work on common goals certainly led to the enactment of the Settlement Act and many other Native achievements.

I think that’s a lesson. Even today, the Native community does much better when its works together. I worked for a number of organizations. I worked for RurALCAP prior to the Settlement Act, and we attempted, in days when there was no real communications -- no television, no radio, no phones in villages -- to try to get information to people about what was happening. RurALCAP continues some of that today in terms of educating people.

I actually went to work for AFN right after the Settlement Act passed. Willie Hensley was president, and I think in terms of implementation, it was a very interesting time. AFN, of course, had been the key organization in getting the Settlement Act passed, but once the Settlement Act passed, leaders from the various regions had responsibilities to go out and set up more than 200 corporations. They had very tight time limits to get land selections made -- I think it was three years for villages and four for regions. As a result, AFN sort of got put aside. There were also some political disputes regarding Don Wright’s presidency, but ultimately, people said well we’ve got to go do our own stuff and AFN, we’ve got a few programs and Willie became president. He called me up one day and said I’d really like some help over here, somebody with some administrative ability and he asked me to work as his vice president. Well, if I’d known how much help Willie needed, I might have gone off to law school instead!

There’s a lesson there. A couple of things happened. One, and Willie won’t tell you this when he’s here next time, but what really impressed me was that because AFN was bankrupt, Willie served most of his tenure without a salary. They finally paid him at the end. He was a legislator at the time, and he skipped along on his legislative side. It was that kind of dedication that was still around. Although the Settlement Act had passed, there really wasn’t much money until Congress authorized a prepayment of $500 thousand for each region. I think that happened about six months after the Settlement Act passed. AFN probably would have gone away if it hadn’t been for the state and federal governments.

A very important part of the implementation is the fight that the Native community had to save the Settlement Act from the governments. It’s a story that I haven’t seen written about much -- the initial attempts by the federal government to write land selection regulations that would have made a third or more of the villages ineligible for the settlement; language that would have blanketed Native lands with free access for any kind of state government easement project, pipeline, road, electrical utility, any of that; language that would have severely restricted where village and regional corporations could select their land, limiting a village’s ability to get key subsistence land.

It was a huge fight. It was a fight that Roger Lang took on -- Willie initially, then Roger Lang -- and it was still going when Sam became president of AFN. It was really the government that saved AFN in my mind, because it became clear by the end of 1972 and early 1973 that there still had to be a single voice for Native people to fight the government, to keep the settlement that they thought they had achieved when Congress passed it in 1971. That fight brought people back to the AFN boardroom, although not all of them all the time, and it brought a limited amount of funding for AFN. It also allowed AFN to be the focal point of the variety of amendments that Sam talked about. I don’t know how many there have been. I have a memo that was prepared for CIRI in 1998 that said that there were at least 29 different amendments -- I mean different times that the Settlement Act has been amended. ANILCA resulted in more than 30 different amendments to the Claims Act alone.

It truly has been a living document, and actually, in my mind, and I’m not trying steal any of Janie’s thunder, but if you look at the trend of amendments, what has happened over time is that the settlement has become less corporate and more tribal. The key changes, are those in the 1991 amendments that Janie will talk about, but even in ANILCA, things like subsistence and the land bank were all moved, I think, away from the corporate model.

I want to talk about two other things. I’ll talk about the net operating loss legislation and I want to talk a little bit about 7(i). The net operating loss legislation, which Senator Stevens helped get adopted, was explained to Congress as legislation that would assist Native corporations, such as Bering Straits and Calista, who had gotten themselves into serious financial trouble early on. It allowed the corporations to essentially sell their losses to profitable corporations in the Lower 48 so that those corporations could write the losses off against their taxes.

I’m not going to spend a lot of time on how that all worked -- it wasn’t a concept invented by the Native community. It had actually been in tax law earlier on. It had been such a drain on the federal treasury that Congress repealed it, but it allowed Native corporations to do this. I think Senator Stevens originally anticipated it would cost the treasury about $50 million, but it cost the treasury substantially more than that. It certainly was helpful to organizations like Bering Straits and Calista, but the organizations that got the most out of it were the most successful corporations, like CIRI and Arctic Slope. There were technical reasons why it worked for them. It worked for Sealaska also, as a matter of fact, and some of the southeast village timber corporations. It created another a huge cash infusion into those corporations, and I think it is an important part of the history.

|

|

|